Ukraine

Ukrainian historian Serhii Plokhy perpetuates the claim that the Russian invasion of Ukraine in Feb. 2022 was “unprovoked” (“The Return of History,” September-October, page 33). But NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg himself refuted that in a recent speech, when he admitted “President Putin declared in the autumn of 2021, and actually sent a draft treaty that they wanted NATO to sign, to promise no more NATO enlargement. That was what he sent us and was a precondition for not invading Ukraine. Of course we didn’t sign that.…So he went to war to prevent NATO, more NATO, close to his borders.”

Illegal? Certainly. Unjustified? Arguably. But “unprovoked”? Hardly.

Plokhy also, echoing the U.S. government position, carefully avoids labeling the events of February 2014 a “coup,” referring instead only to the “Maidan Uprising” and the “Revolution of Dignity.” He’s welcome to use those terms, but the simple fact is that Yanukovych was the democratically elected President of Ukraine, and his unconstitutional removal in the face of armed mobs would certainly have been called a “coup” in any country in which it installed a leader unfriendly to the U.S. But this leader, Yatseniuk, had the vocal approval (and arguably more) of U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland, so a spade is no longer a spade.

Scholars at Harvard should be dedicated to the truth, not, as the article admits, to an “unapologetically Ukrainian perspective.”

Steven Patt, Ph.D. ’75

Cupertino, Calif.

Serhii Plokhy responds: Patt blames the Russian aggression against Ukraine on Washington and NATO. There are several problems with that argument. To imply that the U.S. government under President Obama is somehow responsible for the vote of the Ukrainian parliament to remove Yanukovych from power in 2014 is simply factually wrong. Yatseniuk, whether he had vocal support of Nuland or not, did not replace Yanukovych as the president of Ukraine. Turchynov did. Under pressure from Russia, NATO refused to provide Ukraine with the Membership Action Plan, and Putin himself conceded that the Western leaders had assured him more than once that Ukraine had no chance of joining NATO anytime soon. Yet he attacked Ukraine, using the admission into NATO of Poland and other Eastern European democracies as a pretext. If the Kremlin indeed was concerned about NATO, every single Russian soldier would have been withdrawn from Ukraine and sent to defend the Russian border with Finland after that country joined NATO in April 2023. Nothing of the sort happened. The imperial ambitions of Moscow, not of Washington, are to be blamed for this horrible war.

Campus Conservatives

“The Elephant in the Room,” by Max J. Krupnick (September-October, page 55), discusses conservative undergraduates’ experiences and frustrations relating to campus debates at Harvard. I was particularly interested in the comment that some liberal students have declared certain topics off-limits for debate.

Two quotes from long ago should provide some insight into the merits of limiting debates. First, a quote from Joseph Joubert (1754-1824), a French moralist and essayist, said, “It is better to debate a question without settling it than to settle a question without debating it.” Second, Madison wrote in Federalist 62, “A position that will not be contradicted, need not be proved.”

Ron Dugan, M.B.A. ’67

Spokane, Wash.

It’s hilarious that right-wing Harvard students are whining (yet again) about the university being too liberal. In reality, Harvard is among the most conservative secular universities in the country. Harvard is where The Man is made—the conservative, traditional, corporate, anti-union CEO, white-shoe-law firm son of a son of a CEO. Observing long-standing tradition is Harvard’s brand and promise. They worked hard to get here to embrace it. So perhaps these conservative students are unhappy with the latitude given to ideas not their own. Perhaps they were expecting to stand alone on Harvard’s soapbox. Perhaps they could just stop complaining about being left out. Just kidding—they’ll never stop complaining.

Wendy Moore, A.L.B. ’93

Salem, Mass.

I enjoyed reading “The Elephant in the Room” (September-October, page 55) and was encouraged by thehis call for more open dialogue on the Harvard campus. In reading the piece, I vividly recalled a warm, sunny spring afternoon in 1979 sitting with some classmates when I was a student at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. We had just come from English Lit with a self-proclaimed socialist professor. He had assigned the reading of John Dos Passos’s USA Trilogy and our task was to analyze the work in our final paper. Despite the professor’s teachings, I had vehemently argued against much of what Dos Passos had suggested in his writing. Surprisingly, the professor gave me an “A” with a note saying, “I love when a student takes a different point of view and doesn’t just regurgitate everything I teach.” Apparently, few A’s were given, so coming out of class, my friends were eager to hear what I had written. What transpired was a thoroughly enjoyable debate and sharing of ideas—a time-honored tradition on “The Hill” there, I’m sure, for as long as the university has existed. There were no “safe spaces,” no “trigger warnings,” no name-calling or insults—just great conversation that we all enjoyed and continued throughout the semester.

More importantly, it wasn’t planned—it just happened. I am hoping that these informal interactions still take place among classmates there, but also at places like Harvard, which, despite the leanings of some of its faculty, has always thought of itself as a place for open debate and for the civil sharing of ideas.

I am hopeful that Krupnick’s article is a first step in taking us back to that spirit of lively debate and conversations at Harvard, and that other universities will follow!

Christopher J. Hardwick

Edgewater, Md.

Campus Discourse

We should all be wary when councils and committees seemingly appear out of thin air to address faculty and student complaints of being censored. Rarely are there details about the financial backing of these entities and their connections to similar organizations forming abruptly on campuses nationally (“Speech on Campus,” September-October, page 18).

Using lofty language like “truth-seeking,” “free exchange of competing ideas,” and “intellectual diversity,” right wing groups are demanding that campuses police and shut down protests against racist, sexist, and homophobic drivel that passes as conservative thought nowadays. The efforts are, in fact, just subversive bids to block speech of those alarmed at dehumanizing attitudes permeating political discourse.

Chandak Ghosh, M.P.H. ’00

Chappaqua, N.Y.

Flynn Cratty, executive director of the Council on Academic Freedom, responds: Commitment to the free exchange of ideas is a basic liberal value. Commitment to truth-seeking is a basic human one. The fact that both are often heard today as right-wing dog whistles is good evidence that organizations like the Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard are needed. Our council is not a front for any other group. It emerged organically when a group of about 15 faculty members met to discuss the state of free expression at Harvard. At present, it has more than 130 members with representatives from every Harvard school. Only a small minority of our members would identify themselves as conservatives. We have so far raised enough money to support programming and one half-time staff member. Virtually all our donations have come from alumni who share our desire to see freer speech at Harvard. So long as protests aren’t designed to shout down or intimidate others, you can count on us to defend the right to protest of every Harvard student and faculty member.

We can all applaud the defense of academic freedom, but the article lacked any mention of the responsibility that goes with that freedom. There are faculty members devoted to a political cause (be it on the left or right) and whose goal in class is to convert students to that viewpoint, with a grade being based in part on how well the student has learned the lesson. Or a professor may be seduced by a crank theory, which is then presented as accepted fact in class. Critical thinking by the students is not part of these classes, only getting students to agree with the professor’s opinion. While such cases may not be common, their existence undermines support for academic freedom. The article implies that having a professor’s “lecture slides being examined by administrators” is a threat to academic freedom. Surely that is no different than a professional colleague requesting to see the data on which a research result is based. If I have presented class material in an impartial manner, having others see my presentation is not a threat to my academic freedom. Academic freedom is vital to the educational process, but so is academic responsibility.

Gerald H. Newsom, Ph.D. ’68

Columbus, Ohio

I was encouraged to read of the Council on Academic Freedom’s commitment to “free inquiry, intellectual diversity, and civil discourse at Harvard (“Speech on Campus,” September-October, page 18), but I was very disappointed that such a council was needed. I was a graduate student in the 1960s when the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which had long since ceased being democratic, shouted down speakers with whom they disagreed. I had hoped that such intellectual intolerance had died with the ’60s, but evidently it has reared its ugly head again. I sincerely hope that President Gay and others in the administration will take steps to ensure that Harvard once again becomes an institute of higher learning where academic freedom and the exchange of ideas of all kinds are welcomed and debated.

Alexander P. Shine, A.M. ’71

Carlisle, Penn.

Ethics Education

I read with interest in the news about the new dean of the Divinity School (HDS; online at harvardmag.com/dean-frederick-23). Though I am an alum of the Graduate School of Design, I’ll never think of Harvard without remembering that it originated as a divinity college.

I also try to recall the many illustrious, scholarly, and historical graduates who have played a significant role in the development of our nation and our values. Of course, most unrecognized graduates have made important contributions as well.

However, our nation is now in jeopardy from the criminal, immoral, and unethical behavior of many elite college graduates, including some with degrees from Harvard.

HDS might be a good place to start a discussion and mission to educate all Harvard students in ethics as they apply not only to their professional activities but all of our college and civic lives. I am sure that some Harvard programs have ethics courses that align with professional practices and licensing. However, we are not seeing and hearing enough from our universities on the issues of ethical behavior and what it means to live an ethical life.

I would like to see Harvard do a full-court press on what is ethical behavior and challenge our students, graduates, and leaders with Harvard degrees to behave accordingly, to be examples and representatives of positive ethical behavior, to live their religious values within ethical and moral standards.

David Souers, M.Arch. ’82

Friendship, Me.

Climate Change

One of the unfortunate legacies of Thomas Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions, for all its merits, has been to encourage a sloppy relativism in the popular imagination. Charles Block, writing in to champion relativism in climate science (Letters, September-October, page 6), states that Einstein “disproved” Newton’s theory of gravity. Einstein did not “disprove” Newton—anyone who wants to check Newton’s work is welcome to take measurements as they fall off their chair. Rather, Einstein refined Newton’s model with more complex equations that cover more edge cases more accurately. Such refinement takes place every day in science, including in climate science. But, as inconvenient as it may be to those who prefer weightlessness, the basic facts of climate science—like those of gravity—are settled.

If you search for those “highly credentialed contrarians” Block mentions, you will be hard-pressed to find one who would disagree with this conclusion. Richard Lindzen, an atmospheric scientist who argues that clouds will counteract anthropogenic warming (a view widely discredited), nevertheless agrees that the basic mechanisms of anthropogenic warming are settled fact, and calls those who deny them “nutty.” Celebrity contrarian statistician Bjorn Lomberg, author of The Skeptical Environmentalist, takes the science as settled and argues about economics instead. (“We all need to start seriously focusing, right now, on the most effective ways to fix global warming.”) Physicist Richard Muller, who founded the Koch-funded Berkeley Earth project to address concerns of skeptical non-specialists like himself, came around to the consensus view once he had reviewed the data. (“Following an intensive research effort involving a dozen scientists, I concluded that global warming was real and that the prior estimates of the rate of warming were correct. [And] humans are almost entirely the cause.”)

Questioning and then following the evidence is helpful. Taking a principled (ultimately ideological) stand for epistemological relativism is not.

Brent Ranalli ’97

Boxborough, Mass.

The letters on climate change (September-October, page 6) reiterate what has long been common knowledge—that opinions on climate change (man-made? natural?) are ideologically driven. My ideology, for example, follows the current scientific consensus; the “climate deniers” follow the Republican Party consensus.

What is less known is that there is conflict within the scientific community about what to do about climate change. There appears to be a “purist” ideology that opposes any effort whatsoever as a means for reversing climate change other than reducing or eliminating greenhouse gas emissions. This ideology is dangerous because it requires ignoring an important current fact—namely, the heating effects of albedo-reduction due to rapidly melting Arctic sea ice.

From what I read, I am of opinion that human action restricted solely to cutting emissions, even immediately and to zero, which is very far from happening due to political resistance, would not halt increasing global warming, and resulting increasingly violent and destructive climate change. The recent fire in Maui is a horrible current example.

I would urge Harvard to direct its scientific people to ignore all ideologies and closely examine the feedback dangers of continued melting of Arctic sea ice, and the contrary feedback benefits of any actions to reverse that melting.

Lastly, I would urge that the term “geoengineering,” often used ideologically to denigrate and oppose the merely proposed techniques for refreezing Arctic sea ice, always be applied to the human project, long under way, of burning fossil fuels and thereby flooding the atmosphere with excessive greenhouse gases.

Peter Belmont A.M. ’61

Brooklyn, N.Y.

Shame on you for printing the Jenkins letter on climate change (July-August, page 3). What’s next? Letters from Holocaust Deniers and Flat Earthers? QAnon? The overwhelming scientific consensus and the objective, verifiable reality of climate change are simply beyond responsible debate; denial is unworthy of exposure. The extreme and dangerous weather events now occurring regularly bear sad witness to what scientists—including the fossil-fuel industry’s own scientists—predicted decades ago…before the industry opted for a massive denial and deception campaign. If Veritas means anything anymore, we have to draw the line. C’mon, Harvard Magazine. We expect better.

Kathy Washienko ’90

Seattle, Wash.

KC Golden, M.P.P. ’88

Mazama, Wash.

Betsy Taylor, M.P.A. ’86

New Haven, Vt.

I am somewhat tired of the search for villains and innocent bystanders in the climate apocalypse. It’s a needless distraction from what needs doing now. Who cares what or who started the catastrophes in every day’s evening news? The one thing we know for certain is that we, and those we have engendered and taught and mentored and led, are the only ones who can do anything about it. Time enough for our great-grandchildren’s children to hand out the medals and the coal for their stockings if we last that long.

Marian Henriquez Neudel ’63

Chicago

The recent letters on climate change express different positions on the spectrum of possible views. The reality is more nuanced than extreme positions often advanced. From a geologist’s perspective, the following points, I believe, are fair to make:

•Climate change is real, we are experiencing in now, and it has been brought on by the actions of humans, including but not limited to the burning of fossil fuels.

•Despite wishful thinking, humankind has already passed the point of no return. Natural processes triggered by global warming and other climate change effects already experience will contribute to global warming and related effects through increases in CO2 and methane in the atmosphere.

•Absent extraordinary or unthinkably draconian action, there almost certainly is nothing humankind can do now to stabilize the levels of atmospheric greenhouse gasses, including water vapor, let alone reduce those levels down to twentieth-century historical averages, over a time frame measured in hundreds or even thousands of years.

•Humankind, all eight billion of us, are the culprits, in our understandable desires for higher standards of living. The oil, coal, and other resource companies, electrical utilities, agricultural and airline industries, and other polluters are not the ones to blame, as they have only responded to the demands for their products and services at affordable prices.

•Humans will not become extinct, as we have some control over our environment, although many species may well become extinct.

•Climate change, coupled with fruitless efforts to prevent it and competing efforts by many to deny climate change will result in massive hardship, disease, and starvation worldwide.

•This is a crisis of scope and scale hardly seen before in the modern history of Homo sapiens, and for the good of all must be addressed in a realistic and pragmatic way as a matter of highest world priority.

•Even if further climate change cannot be prevented, its adverse effects must be minimized. This will require unprecedented cooperation of all the world’s nations.

I would like to think that Harvard University and its scholars could take an important role in helping to lead this effort.

William B. Wray, J.D. ’76

Las Vegas

Bravo to John W. Jenkins M.B.A. ‘63, (Climate Change, July-August 2023), for his writing truth to dogma on recent climatic changes. But the truth is still broader.

Terrestrial global variation has been occurring ever since the world was formed 4 billion years ago—not, as some deluded souls seem to believe, for the convenience of the human species, but as the result of cosmic forces and processes that could not care a fig about us or the dinosaurs, trilobites, and slime that preceded us as accidental denizens of this tiny rock. Constant references to changes in “the past 20 years”, or “this century,” or “recorded time,” are for the most part simply silly, irrelevant indicia of their authors’ arrogant unawareness of this history. There have been many extinctions or near extinctions of biotas in the past, and there no reason to think ours will be the last.

The most relevant published and unpublished scientific research on the interaction of (solar) radiation and (atmospheric) molecular species shows that the absorption of solar energy by carbon dioxide has nearly reached saturation and that future terrestrial temperatures from that source will increase only minimally beyond the few degrees already experienced. Observational science, broadly geological sensu lato, tells us we are emerging from a rather mild and short-term (planetary terms) glacial episode and probably returning to the somewhat more temperate conditions typical of pre- or interglacial times. There will be temporary (in terms of Earth time) virgations in this transition, and in land- sea configuration (read: sea-level rise/fall as well as continental shapes), which are rooted in solar and other processes beyond our control; our efforts should be directed to adaptation, not fruitless attempts at prevention of major solar system events.

Priestley Toulmin, A.B. ’51, Ph.D. ’59 (Geology)

Alexandria, Va

Affirmative Action and Admissions

Regarding “The Supreme Court Rules” and the Court’s rejection of discrimination on the basis of “race” (September-October, page 14), Harvard should simply provide affirmative action in favor of competent students who need financial aid (i.e., are not privileged) and who are descended from persons enslaved in the American colonies or states from 1619 to December 6, 1865 (the date of adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment). That description covers some Native Americans, by the way, and maybe some others. What other group, Asians or otherwise, can make a moral objection to that admissions office “tip?”

In reference to the same article’s mention of possible elimination of admissions preferences for “donors” (among others), that is not going to happen. Donor preferences, especially major donor preferences, affect a very small number of applicants, and no university or college, public or private, can afford to eliminate them. Consider a Harvard school whose graduates probably do more than any other on behalf of low/moderate income people, including minorities: the Harvard Chan School of Public Health. It can now do even more (and provide more financial grants, not loans) thanks to a $300- million gift from Gerald Chan (a Chinese American, of course). His children, if he still has any of secondary school age, should get admitted if otherwise qualified. Same for the Harvard Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Science, recipient of a $400-million gift from John Paulson. And I am sure Johns Hopkins, recipient of $1.1 billion from Michael Bloomberg, would also act in the same manner. The gifts are a very big deal; the small to tiny number of admissions “tips” is trivial.

John H. Henn ’64, J.D. ’67

Cambridge

Harvard admissions interviewer 1995-2021

What might Harvard look like in light of the recent Supreme Court decision invalidating racial preferences in university admissions? Consider the University of Michigan, where such preferences were eliminated after a 2006 state constitutional referendum: African American, Hispanic, Asian American, and foreign students (approximately 70 percent of whom are from Asian countries) are, respectively, 5, 8, 17, and 18 percent of students at UM.

Without racial preferences at Harvard, Asian Americans could constitute a higher percentage of College students than currently (approximately 30 percent of the class of 2027 is Asian American according to “The Supreme Court Rules,” September-October, page 14), while numbers of some or perhaps all other racial groups could decline.

UM’s experience shows admissions without racial preferences can result in a racially diverse student body unless racial diversity is deemed to exist only where students mirror the racial makeup of the general population.

Andrew Campbell ’74

Ann Arbor, Mich.

Evangelical Issues

“A New Face of American Evangelicalism” (July-August, page 54) states that the National Association of Evangelicals—of which the subject, Walter Kim, is president—posted an ad in The Washington Post in which it was “resolving, among other things, to uphold a comprehensive pro-life ethic…and resist being co-opted by political agendas.” In view of the Dobbs decision, how are these goals not mutually exclusive?

Cynthia Travis, ’59

San Francisco

The Other Reservoir

Nell Porter Brown’s story about the four towns lost to the Quabbin Reservoir, built 1936-39, and its enticing surrounding buffer area (“The Wonder Out There,” Harvard Squared, September-October, page 8D) mentions the Wachusett Reservoir, built 1895-1906, as having “temporarily assuaged Boston’s need for water” and says that, for its construction, “only a few towns were razed.” In fact, the Wachusett remains a key part of Metropolitan Boston’s water system. All of Metropolitan Boston’s water either flows through, or originates in, the Wachusett’s watershed. While Quabbin water flows through a deep tunnel to the Wachusett Reservoir in the dryer months, in the spring, the tunnel’s flow reverses to direct Ware River water into the Quabbin. There, it is said to be “polished” on a three-year route around a chain of linked islands before arriving at the tunnel’s summer inlet.

Also, although the Quabbin is approximately six times the size of the Wachusett, the population it displaced was only a third greater. As your story suggests, the Quabbin’s Swift River Valley was remote, and by the late 1930s, had suffered both the century long depopulation of New England’s marginal farmland and the deindustrialization that began after the turn of the twentieth century and accelerated with the post-World War I and 1930s depressions. The lost Quabbin town of Enfield was the extreme example. By 1939, its agricultural heyday population of 500 had dwindled to just 18!

Conversely, in 1895, the lost Wachusett towns and mill villages of Boylston, West Boylston Centre, and Oakdale were at the height of their prosperity. Also, unlike the poorly recorded Quabbin demolitions, we have a remarkable archive of 1,400 high-resolution, large format, glass plate photographs of these then still-vibrant communities, recording their six doomed mills and 360 homes, along with schools, churches, and stores—and at times, the people living there.

Dennis J. De Witt, M. Arch. ‘74

Brookline, Mass.

Past president of the Metropolitan Waterworks Museum in Boston and author of Wachusett Water: Dam Reservoir Aqueduct, Construction Photographs 1895-1906

President Bacow

Thanks to for informing the Harvard community about Larry Bacow’s successful presidency (“Short and Sweet,” July-August, page 29). As a Harvard alumnus of Uyghur origin, I am very grateful to him for standing up for the rights of the Uyghur people [see harvardmag.com/bacow-china-19]. I am sure millions of Uyghurs will be grateful too, when freedom shines over them one day. And that great act of kindness will be remembered in Uyghur people’s books and hearts. Why?

I explained its reason in my Crimson op-ed in March 2020: “But in such a time when those with power and fame chose to stay silent or indifferent, President Bacow stood up for justice and subtly expressed his concern for the fate of millions of Uighurs through reading that poem by Ötkür.”

Kaiser Mejit, S.M. ’07

Canton, Mass.

In Service

Bravo to Leo Levenson ’83 for his tribute to—and pride in—his Peace Corps service (Letters, September-October, page 8). Unexpected as it may be to a career-oriented Harvard readership, my four years of active Navy service after NROTC were equally formative, particularly re: core leadership values. To provide only one example, I was awarded two formal Letters of Commendation by two senior Admirals for “Outstanding Performance” in the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, whose iconic “13 Days” included my 25th birthday.

An honors J.D. from Michigan Law, personal awards from three Foreign Sovereigns with a fourth from the U.S. government, and a “Who’s Who Lifetime Achievement” award followed. But all that and more can be traced to NROTC training at Harvard and at sea, and to later leadership by a junior officer before he had entered a grad school or opened a law book.

Terry Murphy ’59

Bethesda, Md.

The Many Harvards

Among the obituaries of many distinguished graduates (including one of my former roommates) in the September-October 2023 issue were the following: three gay men from different classes in the 1950s; a conservative Republican who helped get Clarence Thomas appointed to the Supreme Court and who was recently on Donald Trump’s legal team; Daniel Ellsberg, peace advocate, whom Henry Kissinger called the most dangerous man in America for releasing secret government files on government lies about the war in Vietnam; and Ted Kaczynski, who was known as the “Unabomber” for killing three people and disfiguring 23 others over 17 years. It’s hard to believe such diversity emerged from the same place.

John Andrew Gallery ’61, M.Arch. ’64

Philadelphia

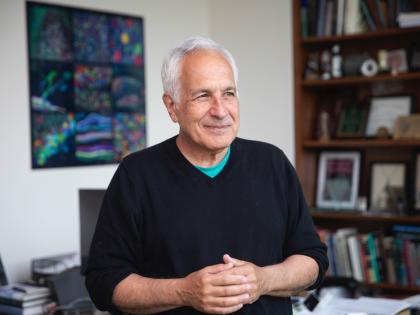

Claudine Gay

When I saw the photo of Claudine Gay on the cover of the September-October magazine, I felt a deep sense of pride in Harvard. Editor John Rosenberg did a masterful job of illustrating why this new president is so well-equipped to lead the university into its fourth century (“The ‘Scholar’s Scholar’,” page 24). What a tribute to higher education and to Harvard individually that she was chosen. It gave me a thrill to be connected to an institution with such high standards.

I grew up in a very Harvard family. My father, Arthur E. Rowse Jr., was in the class of 1918 but left school early to join the Navy during World War I. He served on a mine sweeper in the North Sea doing dangerous work, but made it home and married my mother in February 1919.

I was born in April 1920, during the last pandemic. I joined the Harvard class of 1943 and devoted much time writing sports articles for the Crimson, but enlisted in the army at the end of my junior year just after being named Sports Editor at the Crimson, my dream job, which I was not able to do. In November 1942, my senior year, I enlisted in a program that allowed me to attend Harvard Business School in an accelerated Army program leading to officers’ training in the quartermaster corps. I was called to active duty in 1943 before completing the HBS program. I served in the Second World War in North Africa and Italy until November 1945, receiving four Battle Stars, indicating proximity to the front lines. I received my MBA in 1946.

My brother, Robert M. Rowse, was in the Harvard class of 1947 and joined the Army in 1944. He was killed in the final days of World War II, on April 15, 1945, near the Elbe River in Germany, at the age of 19. The Army’s account of his death says: “During the 9th Army’s drive east of the Rhine”, his unit “was repeatedly given the assignment of wiping out enemy resistance by-passed by the swift advancing American Tanks. While clearing a wooded area near the village of Nutha, [my brother] was hit by enemy fire and died instantly.” He is buried in Margraten Cemetery in the Netherlands alongside other American servicemen. His name can also be found carved in stone, alongside his 1947 classmates who died in the Second World War, on a wall inside Memorial Church in Harvard Yard.

All three of us interrupted our years at Harvard to serve our country, something I am very proud of.

Arthur E. Rowse, III, ’43, I.A.’43, M.B.A. ’46

Chevy Chase, Md.

The appointment of a black woman scholar to Harvard’s presidency is welcome. The selection of a black woman scholar who has built her career on a political agenda of fighting racism and sexism is not welcome. To conservatives, Gay’s appointment will appear to be a cliché. Some of those (conservatives) have raised questions about the credibility of Gay’s research; those questions may be motivated by partisan aims, but so may Gay’s research. Surely there are black women astronomers, artists, engineers, or linguists whose academic contributions have been at least as great as hers. Oh well, maybe Harvard is just trying to add an exclamation point to its identification as a “progressive” institution.

Mimi Gerstell ’66 and A.M. ’91 (Geophysics)

Vero Beach, Fla.

Amplifications

“Reading the Tea Leaves” (7 Ware Street, September-October, pages 4-5), on recent Harvard presidents’ installation exercises, mentioned some of the guest speakers and performers who appeared for Drew Gilpin Faust’s celebration. As she subsequently noted, we inadvertently omitted historian John Hope Franklin, Ph.D. ’41, LL.D. ’81, whom she considers “a hero of mine.” We regret the oversight and are glad to rectify it here and online.

Martin Goshgarian ’62 writes of the September-October Vita (“Arthur Augustus Johnson,” page 40), “The Carter Field mentioned still belongs to the city of Boston, and Northeastern, like other groups, needs a permit to reserve it.”