Hammond Castle Museum is a romantic pastiche of medieval and Renaissance European architecture, a passionate testament to the past where John Hays Hammond Jr. foresaw the technological future.

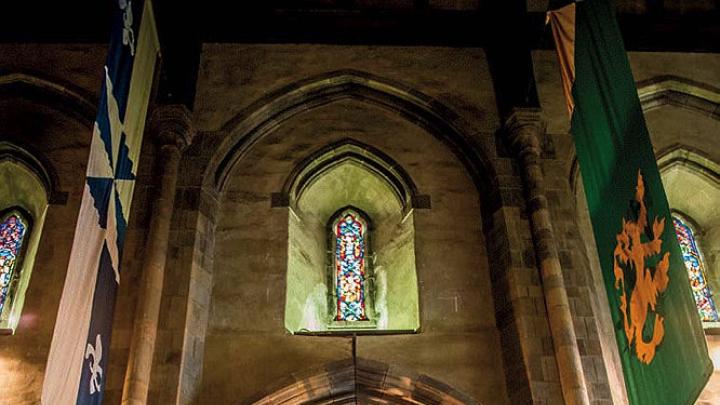

The prolific inventor built the massive dwelling, with its flying buttresses, drawbridge, cloister courtyard, and bell tower perched on Gloucester’s rocky Atlantic coast, in the late 1920s. Then he filled its Gothic-revival rooms with hundreds of artifacts salvaged from the ruins of World War I, opening the showplace as a museum in 1930.

Cape Ann residents, Hammond’s friends, and luminaries including Walt Disney, Marlene Dietrich, Noel Coward, and John D. Rockefeller Jr. flocked to his tours and galas. Disney privately screened his 1940 masterpiece Fantasia in the Great Hall, which doubled, thanks to Hammond’s acoustical innovations, as a concert arena and recording studio where George Gershwin and other prominent musicians performed and played its 7,400-pipe organ. Overnight guests were treated to “playful” pranks. Hammond might appear suddenly in their rooms, late at night, from a hidden passageway, asking his favorite question: “What do you think of the castle?” Or, as visitors gasped in fear, he’d swan-dive into the courtyard’s decoratively green-tinged fountain and fish pond—then surface, smiling: the water was dyed to mask a nearly nine-foot swimming pool. They might also be subject to his in-house “weather system”: doused by rain or shrouded in fog through specially designed steam pipes, which primarily watered his collection of tropical plants.

“He was totally theatrical,” says museum curator and creative director Scott Cordiner. “Bigger than life, like a P.T. Barnum-type.”

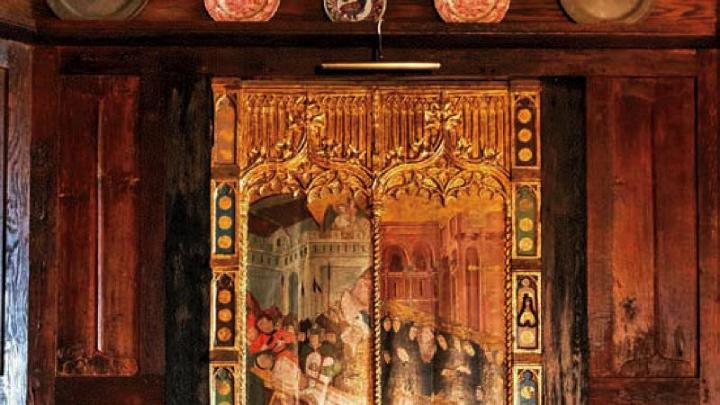

The Gothic-revival and ecclesiastical architecture firm Allen & Collens built the castle, but it was Hammond who specified the transformation of contemporary materials to look time-worn. Scores of craftsmen worked on the house for years, some cleverly beating “the heck out of” the thick wooden doors and stone tiles so they would blend in with Hammond’s actual antiques, Cordiner explains. Workers even carefully carved and polished indentations in the treads of the poured-concrete spiral staircase to make them seem old, and distressed the courtyard’s twentieth-century plaster and timber-framing to better match the three fifteenth-century French village storefronts Hammond bought and had installed.

“Visitors do have a hard time distinguishing between what is an artifact and what is, shall I say, décor,” says Cordiner. “Going through these heavy wooden doors, they don’t know that some of them are actually from the 1400s.” The same is true for more than 50 funerary head stones scattered throughout the museum, including a child’s uncarved (therefore, unused) sarcophagus, and a glass case of human remains discovered by a nineteenth-century German archaeologist who declared, Cordiner adds, that “the fragments came from crew members from Columbus’s first voyage.”

The cathedral-like Great Hall, with Eileen Fenton’s sun room at left

Photograph courtesy of Hammond Castle

Besides being a collector, Hammond was also a Yale-educated engineer, a protégé of Alexander Graham Bell, and ultimately held 437 U.S. patents and 40 foreign ones. Known as “the father of radio control,” he was fascinated by sound and electricity, developing devices and systems for the military and radio-broadcast industry. His pioneering work on remote control was integral to today’s drones and unmanned air and ground vehicles, Cordiner says, and for decades he produced innovations relevant to guided missiles and torpedoes. He also developed the “dynamic multiplier”—the precursor to the modern home stereo system—and more than 200 diverse patents for the pipe organ, piano, toys, robots, cookware, nautical tools, and television.

As early as 1930, Hammond publicly proclaimed “that radio is going to be passé; TV’s going to be king,” reports Cordiner, and he continued to research and design inventions with a team of scientists in castle laboratories until his death in 1965. Hammond, who is buried under a plaque not far from the castle drawbridge, even presciently planned his own legacy. “After I am gone, all my scientific creations will be old-fashioned and forgotten,” he wrote to his father in 1924. “I want to build something in hard stone and engrave on it for posterity a name of which I am justly proud.”

And he was right. Cordiner notes: “We’re constantly having to refresh the world’s memory about John Hays Hammond Jr. He might still be part of the past, but he’s also about today and the future.” The museum is intent on repositioning the site to highlight STEM history and education. Through extensive research and new, expanded exhibits still in progress in the castle’s Invention, Exploration, and War Rooms, Cordiner says, the mission “is to continue to present truthfully Hammond’s art and architecture collection, but, even more so, to build awareness about his scientific contributions.”

Hammond was the son of mining engineer and magnate John Hays Hammond, who earned an initial fortune operating the South African mines of English imperialist Cecil Rhodes. After narrowly escaping a death sentence for his role in the British-backed 1895 Jameson Raid against the Boer republics, he moved the family to England, and then returned to America. There, with friends like President William Howard Taft, he was appointed a special ambassador, and amassed more money through oil-drilling.

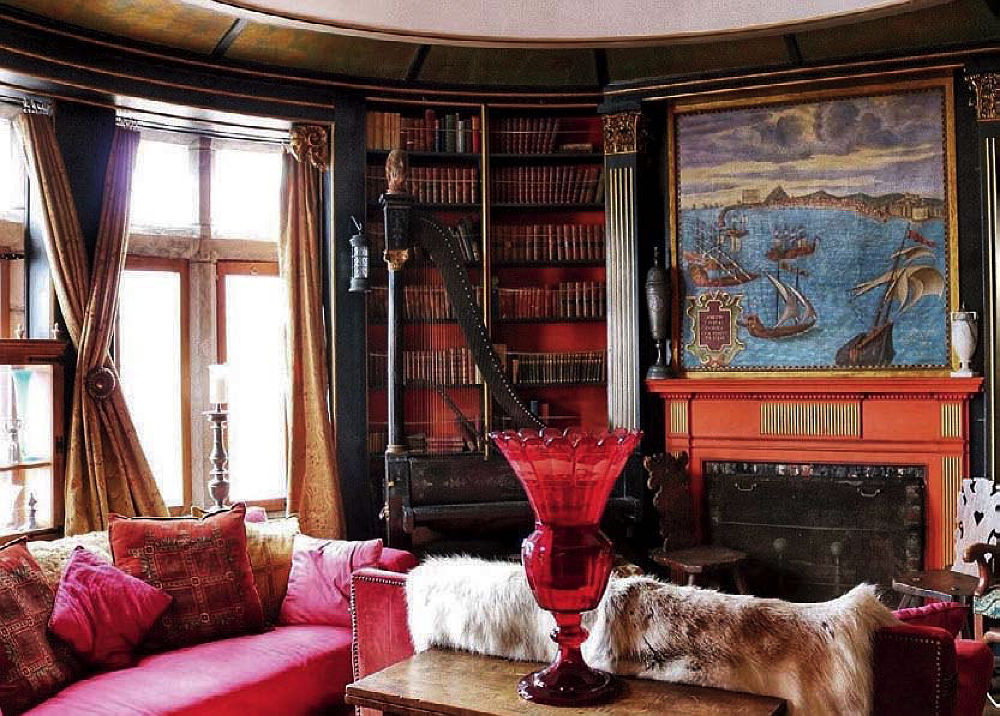

The charming “round room” library features Hammond’s creative acoustics.

Photograph by Loretta Craverio/Courtesy of Hammond Castle

The younger Hammond shared his father’s drive for business-oriented innovation. Although he was wealthy, he worked in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office after graduating from college, learning about the application process and potential commercial markets, and then founded a corporation and laboratory at his father’s Gloucester estate, eventually earning his own fortune through selling his patents, while genuinely enjoying his scientific work.

During the 1910s, he filed at least 75 successful patents toward the development of radio-controlled torpedoes, but with the end of World War I, as Congress moved slowly toward purchasing his military patents, Hammond sought other clients. Most significantly, in 1923, during the heady days of early radio, Radio Corporation of America (RCA) bought 81 of his radio patents and patents-pending for $125,000 and 70,000 shares of RCA stock, Cordiner reports. RCA was among the greatest growth stocks of the time, and Hammond put his new wealth toward construction of his castle.

The Inventions Room details Hammond’s commercial work in sound reproduction and amplification. “It is with television that Hammond attempted to solve one of the earliest problems facing commercial air travel: how does one land at night and during inclement weather?” Cordiner says. “Beginning in 1929 and continuing through 1937, he developed technologies which would allow pilots to land their planes by receiving televised images of the aircraft’s location in relation to the landing strip. Another solution used lights to intersect a safe path for aircraft to follow as the they landed.”

Following a more personal passion, Hammond worked to enhance musical instruments, creating automatic-player systems for the pipe organ and piano, while collecting unusual instruments, like the nineteenth-century claviharp. That harp-cum-keyboard is displayed in the library, a round room with a ceiling Hammond designed to amplify not only musical notes, but also his guests’ conversations. Standing in the middle of the room, one could speak in a way that reverberates, as if from a microphone, as Cordiner demonstrates during a tour. Hammond used it to eavesdrop easily on guests seated around after dinner.

Although nearly half his patents had military applications, he also pursued the civilian market. Early automobile patents signaled the need for an oil change, for example; other patents yielded signage that used electrical dots to form letters; radio channel-selectors allowing listeners to jump automatically to stations playing their preferred music; and television signal-scramblers that required subscription payments to access a program. “His answer to the housing crisis for returning veterans of World War II was a mobile housing system whereby luxury apartments could be moved and inserted into specially designed buildings,” Cordiner notes. “Certainly, some of his patents must be considered as failures, such as his combination lighter/cigarette case, but anyone who has ever stepped on a bottle cap can appreciate his Magnatop Bottlecap Opener, a device noted for its elegant design, which magnetically captured the cap as it was being removed.”

Unlike his father, Cordiner explains, Hammond was not, at core, a capitalist. He fell in love with castles and cathedrals while living in England as a boy, and went on to lead a far more creative, multifarious life than his parents. For one, he married an older divorcée, portrait painter (and social climber, Cordiner says) Irene Fenton Reynolds, whom his mother could never tolerate. The couple were part of the nation’s social and business elite, and especially close to a cadre of artistic and affluent people who summered in Cape Ann—including interior designer Henry Davis Sleeper, who built and lived in Beauport (now a museum owned by Historic New England) and economist Abram Piatt Andrew, Ph.D. 1900. Cordiner says Hammond also had “a longstanding, very caring and loving affair” with another one of their mutual friends in Gloucester, the English-born amateur actor Leslie Buswell. The museum has recently made that fact more explicit—just as Beauport tours now acknowledge Sleeper’s longtime relationship with Andrew. “This is something that has been part of rumors and innuendo in the past, and I believe it is part of his identity and needs to be embraced, explained, and expressed,” the curator says. “The best definition for how Hammond was is ‘pan-sexual’….He loved people based on their personalities.”

The Hammonds themselves were a modern, independent couple. He admired her artistic talents, and they had a loving, compatible, and respectful union, even though she disliked medieval architecture—viewing the Great Hall as a “waste of space,” Cordiner says—and preferred to spend time in the adjacent, more comfortable sun room. Hammond liked to read in a Great Hall alcove, seated in a bishop’s sixth-century marble cathedra (kitty-corner from a fifteenth-century cathedra from Spain’s Cathedral of La Seu d’Urgell). He was often up all night, turning in as she awoke, so they might not see each other for days, leaving notes to communicate.

They also shared an interest in the occult, hosting mediums and seances at the castle. She was a devout spiritualist, and he had long been curious about the capabilities and impacts of sound waves and electromagnetic charges on the emotional lives of human beings. In the early 1950s, he conducted experiments into telepathy using Faraday cages (which obstruct electromagnetic fields) and working with the psychic Eileen J. Garrett. This history, and the traditional cultural attraction of “haunted castles,” explains in part the museum’s previous cooperation with paranormal investigators and the TV show Ghosthunters.

The museum still offers tours focused on spiritualism, and others that emphasize science, sci-fi literature, and the castle’s art and architecture. But during November and December, visitors can enjoy the grand proportions, specially decorated for the holidays, during “Deck the Halls” tours on Fridays through Sundays. (See the website for advance reservations for all events and the museum’s COVID protocols.)

Extravagant décor, the blending of fact and fiction, the push to innovate—all align with Hammond’s vision of his medieval castle by the sea. “People walk past things here and they are not always sure of what they are seeing,” he continues—but they are always surprised and impressed by the castle’s myriad ingenuities. And Hammond would have savored that. Like many of the world’s most successful creative people, he sought to entertain, educate, and advance society through his own faith that whatever he dreamed up could, or someday would, exist.