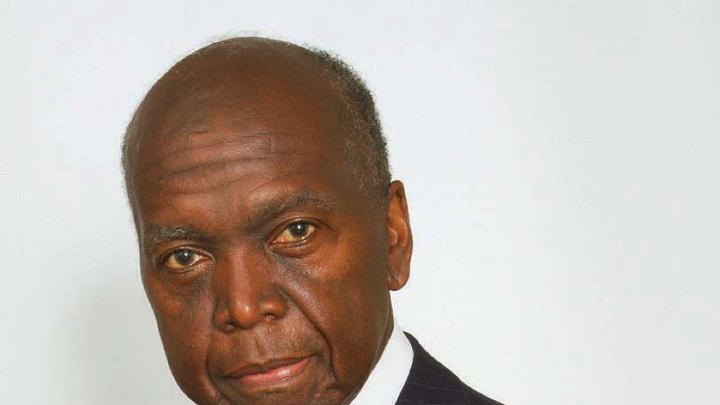

The fourth of seven children, David L. Evans grew up in Arkansas in one of the nation’s poorest counties. His grandmother was born into slavery, and his parents, who died before Evans graduated from high school, were sharecroppers with little formal education. “It’s strange how they believed that there were two sources of magic in the world: education and religion,” Evans recalls. He says he is not as religious as he “should have been,” but he did spend six decades in education, retiring this year after five in the College admissions office.

Evans joined the admissions staff in 1970, entering a very different—and for many, far less welcoming—university. It had not merged with Radcliffe, did not offer such generous financial aid, and had hired its first black admissions officer only two years earlier. (Evans was the second.) In the 100 years since the College graduated its first black alumnus—Richard T. Greener—in 1870, Evans estimates Harvard had admitted fewer than 300 black students. During his 50 years there, approximately 6,000 black students were admitted. The Harvard Alumni Association awarded him a 2020 Harvard Medal in part to recognize his role in that change (see “The 2020 Harvard Medalists,” July-August, page 57).

After earning his bachelor’s from Tennessee State University and a master’s in electrical engineering from Princeton in 1966, Evans lived in Huntsville, Alabama, working for IBM on the Saturn-Apollo project to send U.S. astronauts to the moon. There, he started a college-placement program for black teenagers and helped several enter elite schools, drawing attention from college administrators. In 1970, Harvard offered him a two-year contract as an assistant director of admissions. He became a senior admissions officer in 1975.

During sometimes 16-hour workdays, Evans recruited and selected Harvard applicants of all backgrounds and sought to make the campus more supportive. He became a freshman proctor, living in Wigglesworth Hall alongside students and serving as their academic adviser; from 1973 to 1977 he was also an assistant dean of freshmen (similar to today’s Yard resident deans). His efforts have earned praise from both Harvard—an administrative prize from the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, the W.E.B. Du Bois Medal from the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, in addition to the Harvard Medal—and former students: black alumni endowed a scholarship fund in his name in 2003, exceeding a fundraising goal of $250,000 by more than fourfold.

Evans came to Harvard at a racially fraught time—not long after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and amid disproportionately high death rates for black soldiers in Vietnam. In the 1970s, the campus saw “ugly confrontations” between black and white students—partly, Evans says, because Harvard lacked a structure for grievances and dialogue. In 1981, the University created the Harvard Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations, where Evans served as an adviser.

He sees similarities between then and now, as the nation faces disproportionately more black deaths from COVID-19 and police killings. But recent protests have given him “great hope.” He leaves Harvard a more welcoming and diverse campus, he says, because faculty, administrators, and students “pushed to make it happen.” Such change, he hopes, can happen again. As for himself, Evans hopes retirement will give him more time “to contemplate and convey” the meaning of his journey from a family of black sharecroppers to a Harvard Medal.