On September 23, 1918, when Harvard College opened its doors for the new school year, the Spanish flu had infected hundreds of Cambridge residents. More than 3,000 local children—nearly a quarter of total school enrollment—were reported ill, and Cambridge officials, meeting the day after Harvard classes began, voted to temporarily close the city’s schools. But the University remained open and took few immediate steps to stem the influenza’s spread.

This inaction was rooted less in stubbornness than in uncertainty. Then—as now, during the Coronavirus pandemic—the effect of each public-health policy was not immediately measurable; doctors regularly found new, mysterious symptoms; and for weeks much of the world underestimated the virus’s gravity: in 1918, University administrators and medical experts struggled to predict how an outbreak of Spanish flu, which had just begun earlier that month at two military facilities near Boston, would develop. (A smaller, less deadly, wave of cases had struck the country during the spring and summer.)

Public officials’ early recommendations conflicted. The Massachusetts State Department of Health warned on September 5 that, “Unless precautions are taken the disease in all probability will spread to the civilian population of the city.” But only a few days before Harvard’s fall term started, Boston health commissioner William Woodward had told the public, “I believe the plateau, if not the peak, of the contagion has been reached.” Soon after, with cases in the thousands and new infections still on the rise, he banned public gatherings and ordered schools, theaters, and eventually churches to shut down. The virus would kill an estimated 195,000 Americans in October alone.

Harvard was a very different institution in 1918. President Abbott Lawrence Lowell had only recently required each student to “concentrate” six of his 16 credits in a particular academic division and “distribute” another six credits across at least three areas of study other than his concentration. Final clubs dominated social life. The campus was under constant construction: Widener Library, three additional first-year dorms, the Anderson Memorial Bridge across the Charles River, and an extension to the Peabody Museum had all been built within the previous five years.

Nor did Harvard, at that time, even resemble its normal self: World War I had temporarily transformed the University. Most students had been drafted, and nearly everyone remaining (approximately 1,000 undergraduates and several hundred graduate students) received military training through the Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC), which was subsequently demobilized on December 21, shortly after the November armistice. About half the SATC was housed in the “Freshman Halls,” as well as in Randolph and Westmorly, while the other half lived off-campus. There were similar units for marine and naval trainees . The government also required Harvard to admit some high-school-age students in order to increase the number of men receiving military training, so through December 1918 several hundred high-schoolers attended the College.

It was under these unprecedented and rapidly changing circumstances that Lowell deliberated over whether to delay the school year. Only days before the first day of classes, he wrote to a friend, “I have been talking over the question of opening with some of our medical experts. Doctor Christian felt as you do, that we had better postpone the opening. On the other hand, Doctor Rosenau…thinks it would be a mistake for us not to open on time; that as the epidemic has spread all over the country, there would be no increased exposure from bringing the students here.” He sided with Rosenau: Harvard opened and, for several days, tried to run almost as if there were no pandemic.

By the next week, the outbreak had worsened across the country. Harvard’s Stillman Infirmary was treating several dozen students and Harvard affiliates hospitalized with the flu, and the Cambridge Board of Health had declared a state of public emergency. “The influenza was the worst epidemic which has visited Harvard during the twenty-six years which this department has been maintained. It spread with such rapidity that it nearly swamped us before sufficient force could be organized to handle it,” wrote University medical adviser Marshall Bailey in a report at the academic year’s end. On September 29, Harvard finally began trying to stem the illness’s spread.

George R. Minot

Photograph by the Nobel Foundation/Wikipedia/Public Domain

Administrators called on Doctor George R. Minot, at the time an assistant professor at the Medical School, to lead disease-control efforts. Minot instituted quarantine measures for nearly 1,450 young men, which he later wrote had been possible only because those students, already enrolled in the SATC, were organized into companies and under some degree of military control.

Minot (who later won a Nobel Prize for his work on pernicious anemia) enlisted 13 fourth-year Harvard Medical School students to help him inspect every cadet each morning by taking temperatures and asking about each student’s health and recent interactions—measures reminiscent of the testing and contact tracing Harvard employees returning to work are experiencing now, and that many universities are considering for returning students (if any) this fall. The University also ordered professors to report any incidents of coughing or sneezing, and students exhibiting potential symptoms were to self-report to their company officer or Bailey. Anyone with the slightest illness was placed under observation in an isolation ward in Standish Hall and, if their condition worsened, sent to the college infirmary. In part due to the quarantine measures, cadets were able to continue with daily military drills.

The University took steps to decrease campus density, canceling all classes with more than 50 students and moving all students into either single rooms or two-person dormitories with what Minot deemed to be sufficient space (at least 12 feet by 16 feet). In early October, all students living off-campus were given Harvard housing in order to enhance the quarantine’s effectiveness. School officials regulated dining halls to avoid crowding, and beginning on October 7 prohibited students from entering public spaces, shops, or streetcars, requiring them to stay inside a bounded area within Cambridge.

The strict quarantine and other measures stayed in place until October 26. Harvard recorded 136 cases of Spanish flu through mid-November, and the infirmary treated 258 cases in total that academic year. According to Bailey’s report, five students and one instructor died. Today those numbers would seem staggering—at a time when the undergraduate population was one-fifth its current size, and the number of graduate students even smaller, half a dozen members of the Harvard community died, five of them in a matter of weeks—but Harvard health practitioners at the time considered themselves lucky. “Perhaps the chief reason which kept our mortality comparatively low lies in the Harvard system of medical supervision which places the sick student very early under professional care,” Bailey wrote. The flu killed almost 700 Cambridge residents by February 1919, and nearly 5,000 Boston residents in the fall alone. Peer institutions of higher education were also spared relative to surrounding cities: Stanford and Yale each reported infections in the low hundreds, with Stanford losing 12 students and Yale, three.

None were as successful as Radcliffe College. It enrolled 556 students that academic year, all women who were housed at the Quadrangle. The academic board took immediate measures to control the pandemic.

As the school year began, Radcliffe suspended all social gatherings and, beginning on October 7, cancelled classes for a week. By mid October, all 27 influenza patients at Radcliffe had recovered fully, and no new cases had been reported for two weeks. “The successful results of the week of suspension are the best proof of the wisdom of the decision of the Academic Board,” the Radcliffe News reported on October 18.

Doctors in their gauze masks outside Peter Bent Brigham Hospital

Photograph courtesy of the Brigham and Women's Hospital Archives

Radcliffe’s success was also due to the care and attention of nurses and volunteers. “Life in general looked pretty dark to the unfortunate residents of the dormitories who fell victims to the recent epidemic and were banished to the improvised infirmary in Bertram,” the Radcliffe News reported. “But in the midst of this gloom there shone one ray of cheerfulness—Miss Clark. In those first days, when it was impossible to procure nurses, she carried the whole burden, protecting the general health of the College and saving every patient from really serious illness.”

In mid November, a group of Radcliffe students was even able to stage a farcical play titled “The First Hundred Years.” The plot was simple: a group of young men who return to college, only to be kissed by Ina Flu Enza, begin to sneeze, and must be moved to the Bertram Hall Pest House. Musical numbers included “There’s a big fat germ waiting” and “Cough cough, we’re coughing all day.”

Harvard and Radcliffe both managed to limit the influenza’s spread among students somewhat by changing or curtailing operations, but Harvard hospitals and clinics did not have that option. The Harvard-affiliated Peter Bent Brigham Hospital (a predecessor of today’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital) lent all of its resources to Boston and Cambridge in combating the flu, taking on patients in critical condition who could not be cared for at home or who would put relatives at risk by staying home. Of 557 patients the hospital received, 153 died. “Many died in a few hours after being brought to the hospital. The wards were filled with patients extremely ill with the pneumonia that accompanied influenza. More than half of our nursing and medical staffs themselves had influenza,” wrote Henry A. Christian, the physician-in-chief. Staff wore masks, caps, and gowns, and any sick doctors or nurses were immediately put on bed rest. Only one nurse did not recover.

Public-health practitioners led the charge against the disease. The Brigham relied heavily on its nurses and nursing school during the epidemic, as workdays increased to 10 hours and younger nurses took on the responsibilities of head nurses who had fallen sick. The hospital’s acting superintendent of nurses praised her students’ and nurses’ efforts, writing, “Enough cannot be said of the faithfulness and devotion of the nurses able to continue on duty during this period.”

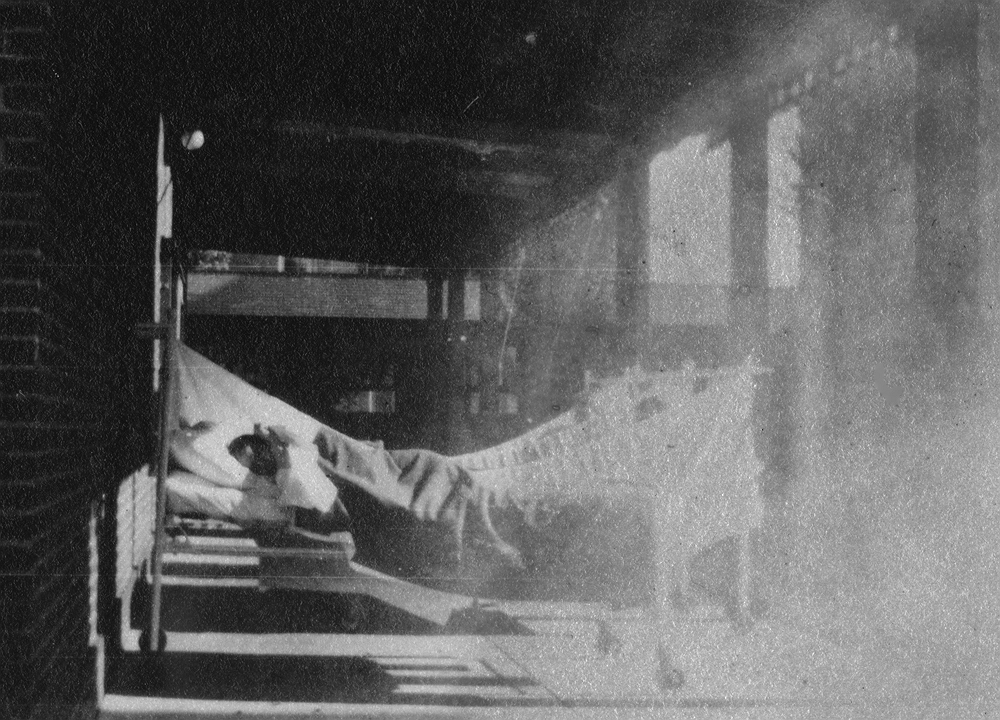

A flu tent at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in 1918

Photograph courtesy of the Brigham and Women's Hospital Archives

As Harvard now weighs re-opening scenarios for the fall of 2020, trying to stay a step ahead of COVID-19, thousands of students have wondered what could have been and what will be—questions their predecessors also asked, and tried to answer, more than a century ago. “We are only doing our patriotic duty in paying particular attention to our own healths, in order to keep fit for the ordinary things that have to be done every day, and to lessen the strain on the already overtaxed doctors and nurses,” one student wrote in the October 4, 1918, Radcliffe News. “The fact that there are a good many colds, and several cases of influenza itself among us, need not cause undue nervousness. The proverbial ounce of prevention is still worth its weight, and with perhaps a little more than ordinary care, we who have just returned from a long vacation, should have no fear.”