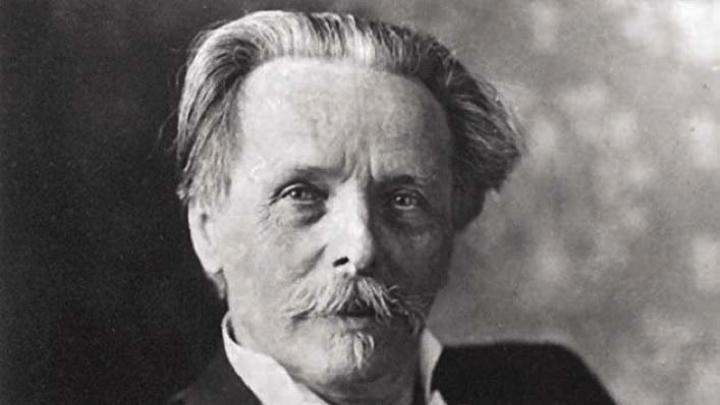

The most popular German author most Americans have never heard of is Karl May, whose adventure novels have sold more than 100 million copies in the German-speaking world. Though the son of poor weavers in Saxony, May (pronounced “my”) nevertheless received supplementary training in music, English, and French in school; meanwhile, his avid reading of popular robber tales, and a visit to a puppet theater at the age of nine, no doubt stimulated his childhood imagination. He trained as a teacher, but lost his license after being charged with stealing a roommate’s watch. Banned from his profession, he became a con man, impersonating among others a doctor and police detective, and spent several years in jail in his twenties. Perhaps these fictional self-projections were the embryonic beginnings of his becoming a best-selling novelist.

The books May wrote in his prime that made him a publishing phenomenon are riveting travel narratives set around the world, but mostly in the Middle East and the Wild West, where his fictional alter ego performs daring actions almost nonstop—a type of mid-nineteenth-century German Indiana Jones. These tall tales playing out in a picaresque fashion in landscapes vividly imagined in great detail, from the Rocky Mountains and American prairies to the sands of the Sahara, have been a perennial favorite of young readers in Germany and beyond. Albert Einstein acknowledged that “my whole adolescence stood under his sign. Indeed, even today, he has been dear to me in many a desperate hour.” Arnold Schwarzenegger stated that May’s books “opened up my world and gave me a window to see America.” But another young Austrian was also a fan: Adolf Hitler.

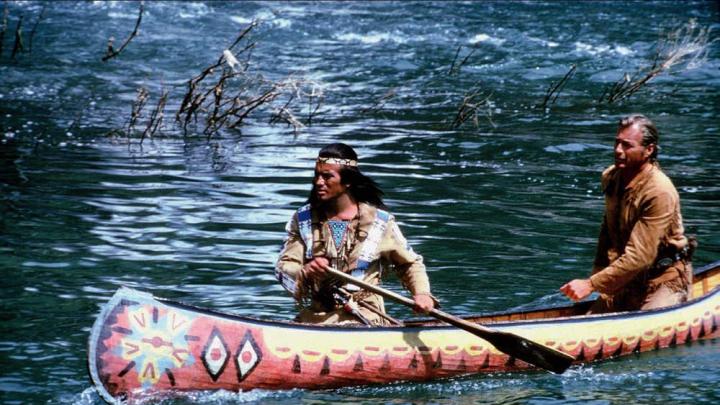

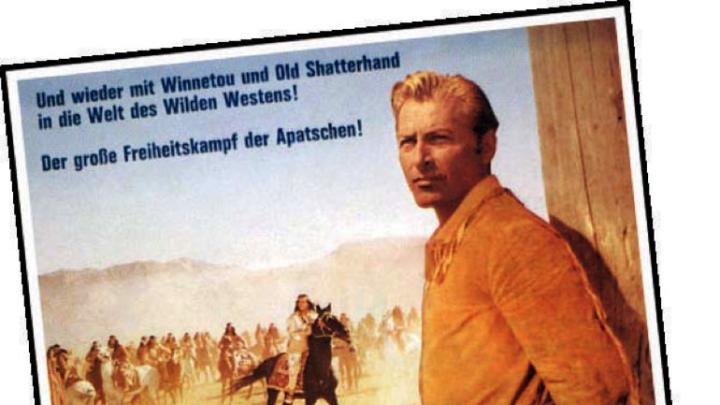

The Last Shot (1965)

Photograph by Allstar Picture Library/Alamy Stock Photo

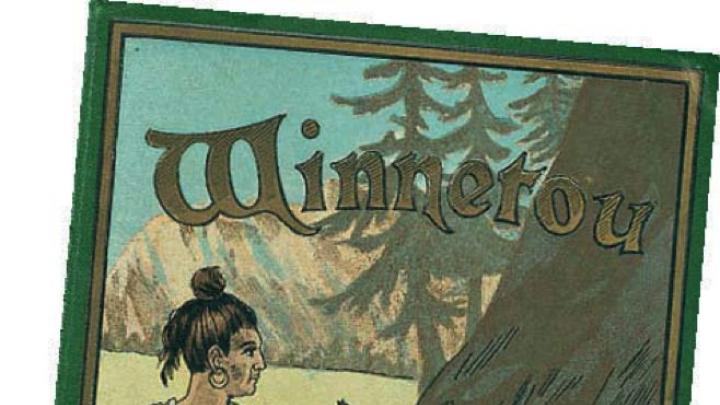

May spent his years behind bars as a voracious reader, using the prison library to prepare himself for a literary career. After his release, he emerged in his thirties as the editor of several journals as well as the pseudonymous author of stories in magazines and of pulp fiction novels. He began writing full-time in 1875, and hit his stride as a hugely popular author in mid-career. The first of his famous three novels about Winnetou, the Mescalero Apache chief, and his German friend and sometime sidekick, Old Shatterhand—May’s most heroic alter ego—appeared in 1893, when he was 51. His novels have been translated into many languages, and a number of films are based on them. A Karl May Museum opened in Germany in 1928, there are annual Karl May festivals, and a publishing house, Karl May Verlag, keeps his works in print. (None of this German May fervor, though, has had any notable impact on the anglophone world, which has its own repository of Wild West fictions, from James Fenimore Cooper—a major influence on May—to Zane Grey and classic films and television shows. What’s more, some of May’s legendary “Westmen,” like Old Shatterhand and Sam Hawkens, were actually Germans.)

Though May’s tall tales are full of gore and gun smoke, they are also consistently informed by a Christian message: Old Shatterhand will kill only as a last resort. He prefers to shoot those trying to kill him in the hands or knees. May’s most idealized Indian character, Winnetou, dies as a Christian after a moving conversion experience: “I believe in the Savior. Winnetou is a Christian. Farewell” are his final words.

From a contemporary perspective, this conversion seems an uncalled-for abdication of his Native American identity, but part of May’s idealization of Winnetou is the intense homosocial bond between him and Old Shatterhand as they become devoted and loving “blood brothers.” This happens after the “greenhorn” Shatterhand is captured by the Apaches on his first venture into the Wild West, as a surveyor for a railroad company planning to lay tracks across tribal territory without permission. Nearly killed by Winnetou, Shatterhand gains his freedom and the trust of the Apache chief and his tribe through his heroic deeds and devotion to them. The story of their friendship up to Winnetou’s untimely death is both highly sentimental and moving. In May’s overarching Christian and Eurocentric vision, his sympathetic portrayal of Native Americans in their inevitable decline as they war among themselves, only to be marginalized and destroyed by the inevitable advance of the whites into their shrinking territories, is a tragic one.

May’s colorful and dramatic presentation in the Winnetou saga of “the Wild West around the year 1868,” a landscape imagined only from his wide reading, is thoroughly inflected, not surprisingly, by the colonial and racial assumptions of the nineteenth-century imperialist European culture that shaped his vision of a place he never visited. But despite these Victorian-era stereotypes haunting his novels, his fictional paean to his “dear, dear Winnetou” was a powerful protest against what he saw as the genocidal treatment of Native Americans. Their demise is symbolized by the tragic fate of Winnetou, that “splendid human being,” who was “eliminated…just as in short order the entire race will be eliminated, whose noblest son he was.”

In his later years, having achieved wealth and fame with his riveting adventure stories, May turned to writing tendentious philosophical novels with allegorical speculations about humanity’s rise from evil to good. In the spring of 1912, shortly before his death, he delivered a public lecture in Vienna, “Up into the Realm [Reich] of the Noble Humans,” in which he paid tribute to the peace movement and the pacifist ideal of Nobel Peace Prize winner Bertha von Suttner, who was a guest of honor. In this lecture, May declared that human worth was not defined by skin color and championed an evolutionary ideal of a noble humanity. The young, impoverished Hitler attended the lecture, but seems to have appropriated May’s pacifist “Reich” ideal for his own infernal ideological purposes, failing to process May’s powerful Christian and pacifist message against genocide.