In the finale of the Netflix series Living with Yourself, Paul Rudd’s character gets into a fight with himself—or, rather, with a clone of himself. That new-and-improved version has spent the previous seven and a half episodes tormenting the original, a sad sack named Miles, by outshining him at work, at home, and pretty much everywhere. When they finally come to blows in the climactic scene, Miles and New Miles—both played by Rudd—destroy an entire apartment, leaving furniture smashed, sheets torn, packing peanuts strewn all over: a careening, spectacular mess.

And every second, of course, was meticulously choreographed. For that, the show’s creators turned to Kuperman Brothers—the eponymous enterprise of Rick ’11 and Jeff: choreographers and directors with third-degree black belts in Kenpo karate and a growing list of screen and stage credits. The pair devised and rehearsed an action sequence emphasizing the idea of two equally matched—and equally awkward—fighters whose lives and identities are inextricably joined. During the fracas, the two Mileses sometimes seem to come together like a seesaw, and when one tries to hurl the other over his head, the force hurls them both into a circular tumble. At one point the two characters get twisted up together inside a bedsheet; later, facing off like mirror images, they push off each other with one foot, a double-kick move that sends each falling backward.

During the four-day shoot, as Rudd filmed the fight, first as one Miles and then as the other, one or the other Kuperman subbed in to stunt-double as his opponent: two brothers who look almost like twins (Rick and Jeff are only 13 months apart) standing in for doppelgangers who look, and fight, like brothers. “It was a really cool process,” says Rick Kuperman, “creating the action of these two leads, and also figuring out how it translated to the camera, how the camera would move to capture it.”

For the Kupermans, choreography came gradually, although dance started early. The two grew up in Toronto, where an interest in gymnastics quickly led to ballet and then tap, jazz, and contemporary dance. They branched into acrobatics and parkour, and then martial arts. The dance studio where they spent much of their childhood was an unusually nurturing place for young boys, Rick says: “There were a lot of male dancers. Oftentimes, you’re lucky if there are one or two guys. But there, it was the kind of thing where masculinity and movement were naturally combined.”

After high school, Rick, who is older, came to Harvard and Jeff went to Princeton. Both kept up their dance training alongside their other studies (Rick graduated with a concentration in psychology: “Incredibly relevant for work in the arts, process-wise”). They were learning about the greats of modern American dance—Isadora Duncan, Martha Graham, Katherine Dunham, Paul Taylor—while auditioning for performances and experimenting with choreography and directing at their separate campuses. They converged every summer in New York, where they put on a show, sometimes two, at Sightline Arts, a production company and arts incubator co-founded by Rick’s friend Calla Videt ’08. Their formal partnership grew out of those yearly convergences. “We just found that the work was better when we were together,” says Rick, “and that it was also more fun to make.” Safer, too. With his brother anchoring him, Rick says, he felt secure taking artistic risks and articulating wild ideas. “You have the freedom to go to the outer edges of your creativity.”

Kuperman Brothers incorporated in 2012, and the pair’s burgeoning repertoire now includes work in television, films, commercials, music videos, and theatrical productions. In 2016, they choreographed some 20 dancers performing to the Phish song “Petrichor” as part of a New Year’s Eve concert in Madison Square Garden. Early last year, the Kupermans choreographed a production of the musical Alice by Heart, a reimagining of Alice in Wonderland that places the protagonist in a London Tube station during the Blitz. The result, developed over four months in what Rick calls a “choreographic lab” with a team of collaborators and performers, won several awards. More recently, they choreographed Cyrano, a moody musical adaptation of Cyrano de Bergerac that starred Peter Dinklage, with a score by the rock band The National; they also choreographed a forthcoming Miramax film, Silent Retreat, about a bumbling group of four people who go to upstate New York for three days of silent meditation. It becomes a silent comedy about 20 minutes in, Rick explains: “Our role was to create some of the physical comedy,” drawing on the traditions of Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and other silent-film comedians.

Humor—physical, ironic, witty, poignant—is a common thread through their choreography. Another is the importance of story. “In every format,” Rick emphasizes, “our principal goal is to tell a compelling story. That’s always been my strongest interest: not movement for movement’s sake—although that is often brilliant and virtuosic and can bring me to tears—but creating a movement language that is part of a narrative structure, that helps drive a story.”

This is especially visible in the films and music videos they’ve increasingly begun to direct: an advertisement for a tea-of-the-month club that pits Earl Grey in a powdered wig against an adventurous tea-drinking everyman; a short dance film about four factory workers (the Kupermans star as two of them) who turn on each other under the constant, paranoia-inducing eye of management’s surveillance cameras; a music video in which a wedding devolves into a wildly kinetic pew-clearing brawl. As choreographers and directors for film, “all of a sudden you have another dance partner: in the camera,” Rick says. “That relationship of the movement of the camera to the action of the performers opens up a whole other world of storytelling opportunities.”

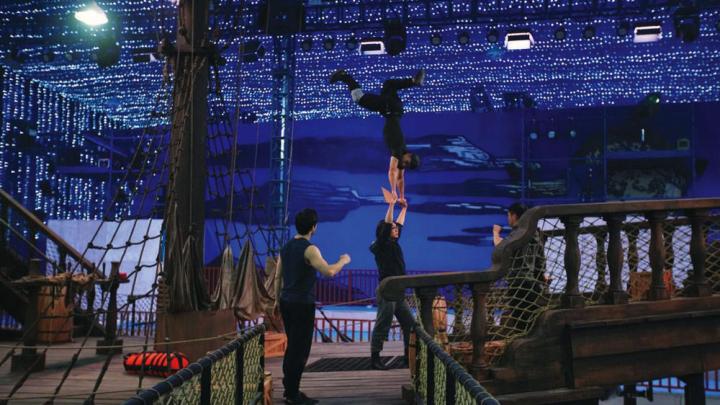

Another narrative format they’ve experimented with is immersive theater, in which the fourth wall between audience and performers breaks down, as viewers enter the space that the actors and dancers inhabit. In 2017, the brothers choreographed a production in Beijing called Neverland, in which audience members could experience the Peter Pan story from different perspectives: the Lost Boys, the mermaids, the fairies, the natives, the pirates. Each perspective told a different story. “Figuring out how to move all these bodies through the space and have them converge at the exact right moments so that a scene can take place, and then disperse and continue on their tracks … that can be very complex and very rewarding work,” Rick says. “Again, it all comes back to movement as a story.”