W

hen the batteries of his three-year-old Apple Airpods began to fail, Geoffrey A. Fowler ’00 took them to the Apple Store. A repair was impossible, an Apple Genius told him. New ones would cost $149.

Others might have rolled their eyes and dug into their wallets. But Fowler, The Washington Post’s technology columnist, had some questions. How could Apple, a company worth more than a trillion dollars, have no way of repairing the battery of a product used by tens of millions? During the next few weeks as he dogged Apple, via email, for answers about the durability, sustainability, and replaceability of one of its flagship products, Fowler also gathered sharp dental tools, borrowed a special plastic-slicing knife, and performed an “Airpod autopsy” on his wireless headphones.

A few days later, with enough of his questions reluctantly addressed in corporatese, he posted the pseudo-medical results as a column and video, narrating his predicament and explaining Apple’s lackluster AirPod repair policy. “We shouldn’t let Apple turn [headphones] into expensive, disposable electronics,” he argued in his column. “It’s hurting our wallets—and the environment.”

Based in San Francisco, Fowler joined the Post in 2017, after 16 years covering consumer technology, Silicon Valley, and China for The Wall Street Journal. Unlike some tech reporters, he’s not particularly interested in what he calls the “Game of Thrones aspect” of tech journalism: who’s up, who’s down, who’s a billionaire. His approach is more anthropological, filled with questions about technology’s impact on everyday life. He compares his role as columnist to that of a “relationship counselor” between users and technology. “So, is this really working for us?” is often the question at issue.

Lately, his main interest has been what he calls “the secret life of your data”: the myriad ways industries harvest personal information while concealing the extent of the snooping. His videos and columns are filled with “experiments” he uses to peel back the curtain on typical tech practices.

When a giant Apple ad proclaimed, “What happens on your iPhone, stays on your iPhone,” Fowler fact-checked it. He asked a friend—a former National Security Agency staff member—to hack his iPhone and see what happened to his data. In one night, his iPhone shuttled information to a dozen marketing companies, research firms, and other organizations. Yelp, a crowd-sourced restaurant reviewing service, received a message that included his IP address once every five minutes. In just one week, his iPhone fed information to 5,400 data trackers, mostly through apps. “Isn’t Apple supposed to be better at privacy?” Fowler wrote.

In another column, he examined thousands of recordings that his Amazon Echo had kept of him during a four-year period. People can manually delete the saved recordings, but they can’t stop Amazon from collecting and sending them to employees tasked with improving the device’s artificial intelligence. “My life, I think it belongs to me. They think it belongs to them,” Fowler says, his voice rising in semi-amused frustration. “I have a big problem with that. It’s my life, not their life!”

Behind the serious subject matter, and his very real concerns about data privacy, Fowler’s coverage retains a sense of humor. Readers can tell that he actually enjoys bugging Apple representatives with emails, knowing that even after weeks of pressure, their responses will be woefully inadequate. His favorite part of journalism has always been the exploration and discovery–chasing an elusive question to the furthest extent possible. (Sometimes that question isn’t especially substantive. In one video, he asks people on the street if they can flip open Samsung’s Galaxy Fold—a $2,000 phone with a massive folding touch screen—with just one hand. It’s not easy.)

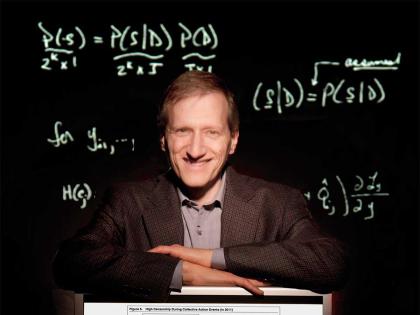

In his videos, Fowler’s round face appears both amused and incredulous, his mouth on the verge of a knowing smile, as if he’s asking, Isn’t this stuff comically insane? Though an early adopter of personal technology, he’s managed to keep a critical distance as tech has become omnipresent, approaching it not as a “consumption device” to distract and entertain, but as a tool.

When Fowler was six, his father, a professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina, brought home a brand-less computer assembled at a local tech store in Columbia. Fowler took to the massive device quickly as a drawing tool. His first composition, executed on a now-obsolete program named GEM Draw, featured a self-portrait: a boy with a square torso wearing a pink-patterned shirt, with a lower body resembling a tuning fork.

Every month, the family received PC World, a magazine thick with ads for computer components. Fowler remembers the consistent effort required to keep the device up to date, replacing and installing new parts. At the time, using a computer required some knowledge of what was going on inside. With user-friendly options today, it’s easier to operate the devices, but harder to know what’s happening within. Fowler thinks some of the opacity is intentional: “They don’t really want you to know what they’re taking, who they’re sharing it with, and what they’re doing with it.”

When he was 10, his mother, a librarian, encouraged him to apply for the Mini Page Press Corps, a program led by The State, a respected local newspaper. “Basically, they hired 10-year-olds to write stories,” he says. “And I loved it.” He recalls the staff putting a surprising amount of time into training ’tween reporters. Through this job and summers at journalism camp, he fell in love with the sense of wonder that journalism fosters: “going someplace new, having to figure something out.”

When he arrived at Harvard on the cusp of the dot-com boom, his interests in journalism and computers melded. He installed Ethernet technology in student dorms, and was enlisted when the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and the College wanted websites. He distinctly remembers meeting with an administrator and debating whether to put each House’s facebook online. They decided it was a terrible idea. “So that, obviously,” he says, laughing, “was the same idea Mark Zuckerberg [’06, LL.D. ’17] eventually had, and which became the world’s fifth most valuable company.”

As a Ledecky Fellow for this magazine during his senior year, Fowler often addressed the rising allure of the tech world, and the promise of riches. “The commercialization of the Internet has fabricated an ethos of e-commerce so powerful that computer science and finance now share a common battle cry: ‘Who wants to be a millionaire?’” he wrote. In 1997, when The Harvard Crimson got serious about a Web presence, Fowler and another Ledecky Fellow, Jennifer 8. Lee ’99, became the paper’s first webmasters. (Lee, now an incorporator of this magazine, is the subject of “Of Dumplings, Bok Choy, and the Politics of Emoji,” 2/14/19.)

Despite all this, Fowler never considered concentrating in computer science, or even taking a class on the subject. “For me, it’s always been about what the things do, or what you can do with the thing, rather than the science of the thing—like how it works in and of itself.” Instead, he took an introductory anthropology class and found his intellectual home. While editing the student magazine Diversity and Distinction, he aimed to merge an anthropological way of thinking—trying to understand something through a new set of eyes—with narrative storytelling.

After graduation, he spent a year at Cambridge’s Trinity College, earning a master’s degree in anthropology, but also freelancing as a writer. An internship at The Wall Street Journal led to his being hired as a news assistant on the foreign desk. His first day of work was September 11, 2001; the paper’s office, located beside the World Trade Center, was severely damaged and filled with ash. Fowler, on his way to work by subway, rushed back home before the towers collapsed.

As the United States prepared to invade Afghanistan, Fowler helped coordinate Journal reporters covering the region. During the 2001 anthrax attacks that targeted politicians and journalists, he was in charge of opening the newspaper’s mail. Despite such turmoil, he stuck with his focus on tech—and anthropology: his first front-page story explored the historical development of human thumbs and their rising importance in texting culture.

The following year, he was promoted to a reporting role in Hong Kong. As international companies poured in during the decade, Fowler covered business, media, advertising, and the early rise of the Internet in China. He also got to cover the 2008 Olympics. But after seven years in Hong Kong, he was ready for a new challenge. When a reporting slot covering tech and national news in the Journal’s San Francisco office became available in 2009, he took it.

That year put him, once again, at a news epicenter, covering e-commerce and startups, the rapid growth of Facebook and Apple, and the smartphone revolution. When Steve Jobs died, Fowler was the fill-in Apple beat reporter. In 2014, an opportunity opened up to write about technology in the first person: “One day they snapped a switch and said, ‘Okay, sound like you!’ and that causes an existential moment of, like, ‘What do I sound like? Who am I?’” In his new role as personal-technology columnist and reviewer, he covered tech’s consumer side: How does this product affect you? In 2017, the Post called to ask if he could do him for them. As part of an expanding technology team there, he had even more freedom to explore his role of consumer-advocate.

In person, as in his writing, Fowler is funny. He’s prone to breathless, amusing rants when discussing the way consumers’ data are being collected and distributed. (Walking through the San Francisco streets, he promises to make a scene outside Facebook’s office. “I can shake my fist and say, “‘Damn you, Zuckerberg!’” he jokes, with fists dramatically clenched.)

But the substance behind the words and his most pointed columns is no joke. Fowler’s reporting dissects the privacy policies and practices of some of the world’s biggest, most powerful, and influential companies, and challenges them to do better. In one recent column, he lists the 15 most egregious default privacy settings at Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Apple—and then tells readers how to change them. In another, he uses brand-new credit cards from Amazon and Apple to buy a single banana from Target, then tracks how the two industry giants broadcast his data to a host of private companies. Even when he’s not working, his trusty group of electronic assistants—a Sonos speaker, Google Home, Apple HomePod, and Amazon Echo—sit on his living room table, serving as constant sources of unnerving inspiration. Although they are supposed to function only upon hearing an explicit voice command, the sounds of television shows and private conversations frequently trigger them. “I’m waiting for the day to come when they start talking to each other,” he says. “And then they don’t really need me anymore.”

Fowler believes it likely that some people in the Bay Area consider him too negative about technology. After his years of consistent and thorough coverage, the response he often gets from tech companies is one of vexed recognition. “I’ve actually had them say, ‘We know what you do,’” he says, laughing. “And I’m like, ‘Great! If you know what I do, then we can save a lot of time here. Just give me the answers I’m looking for!’”

But behind even his most critical columns is a sense of hopefulness. Fowler thinks that tech companies can change how they deal with privacy. “These billion-dollar corporations are giving us a false choice between having our lives surveilled and monetized—or living in the Stone Age,” he explains. “They’re like, ‘You either allow us to collect all this data and do what we want with it, or you can’t use artificial intelligence, you can’t use a voice agent, you can’t have all these things.’”

“That’s the cognitive dissonance of being a modern consumer in 2019,” Fowler says. “You can wonder at the new thing and also realize it’s bringing peril into our lives. That’s the tension that I often find myself in, as a writer.”

What if Google just charged five dollars a month for the technology, he wonders, instead of tracking our data through its home assistant? He notes that some of these companies have amazing—and amazingly helpful—artificial intelligence. Why should capitalizing on people’s private lives be the only way to make money? “That’s the cognitive dissonance of being a modern consumer in 2019,” he says. “You can wonder at the new thing and also realize it’s bringing peril into our lives. That’s the tension that I often find myself in, as a writer.”

Fowler sees potential danger when governments have more tools to harness data. As he speaks, massive protests wrack Hong Kong, his “other hometown.” The familiar backdrop of tech surveillance lies in plain sight, with protesters wearing masks and shrouding themselves with umbrellas to escape detection by advanced facial-recognition software: technology deployed to intimidate and stifle expression. Recently, he has noticed his friends from Hong Kong wiping their social-media accounts clean, worried that their records could be searched and potentially used to put them in jail if they travel into mainland China. “When governments have data about your whereabouts and about what you’re up to, they can use that however they want,” he says. He thinks about his new Google Home Max, a talking speaker with facial-recognition software. “Is there a record now of every time I’m at home?…Do the police get to have that record?”

Even as he challenges companies’ lack of transparency and the potential for information abuse, Fowler thinks that increasing pressure can rein in surveillance capitalism. “Younger people know enough about the Internet and the power of data, that I think they’re going to reject it,” he says. This unease has prompted the growing pushback against Facebook and Instagram. Fowler’s purpose is to show people that the system doesn’t need to stay the way it is—that citizens and consumers have a right to demand some control over their lives: “I think as a society, we’ve been sort of distracted by the sparkly, shiny aspect of what this can do for us. Maybe we haven’t always realized what we’re getting into. That’s the great reckoning that’s happening right now.”