“The drums are calling out your name,” Ali Sethi ’06 exhorted the gyrating audience in Sanders Theatre, as he and his bandmates wound toward the climax of the night’s final number, a song with roots stretching back to the medieval period in what is now Pakistan. Some listeners were already on their feet, and a handful of students were dancing on stage. Behind Sethi, the tabla player’s fingers flew across the drums, pounding out a rhythm that was intricate, ecstatic, irresistible.

It was the headlining concert at Harvard’s ArtsFirst Festival last May, and the song, “Dama Dam Mast Qalandar,” is a South Asian favorite, with a melody composed in the 1960s and lyrics drawn from a thirteenth-century poem honoring the Sufi saint Lal Shahbaz Qalandar. The work is often performed at Qalandar’s shrine in southeastern Pakistan, where pilgrims commune with the divine by taking part in dhamal, a whirling, pounding, trancelike dance. Inside the song’s feverish rhythms, Sethi told the audience, traditional boundaries among worshippers—class, caste, gender, geography—break down.

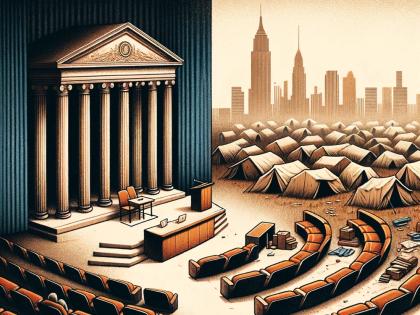

Something similar seems to happen with Sethi’s music: boundaries fall away—between past and present, earthly and transcendent, between art and religion and politics. “We are many and we are one,” he says. A singer classically trained in Pakistani traditional music, whose voice can shift from plaintive to raw to warmly intimate, Sethi (pronounced say-tee) has become a star in (and, increasingly, beyond) Pakistan. Since 2012, when he appeared on the soundtrack for the film The Reluctant Fundamentalist (directed by Mira Nair ’79), he has toured internationally and been a regular presence on Coke Studio, Pakistan’s popular live-music television show. This past April he made his debut at Carnegie Hall as one of three soloists in Where We Lost Our Shadows, a multimedia orchestral work co-created by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Du Yun, Ph.D. ’06, about human migration and the flight of refugees. And for the past several months, he has collaborated with Grammy-winning musician and producer Noah Georgeson on an album, to be released by summer 2020, that combines classical South Asian music with his own songwriting.

Born and raised in Lahore, Pakistan, he is the son of dissident journalists; since the 1970s, his father has been jailed repeatedly, and in 2011 the family fled the country for more than a year after receiving death threats. Sethi arrived at Harvard in September 2002, exactly a year after 9/11. “Everywhere I went, people were kind of cagey about Muslims,” he recalls. “Like, ‘Ooh, what do Muslims really believe?’” But even as he felt pressure to explain, he knew a part of him was searching, too: “There was this wanting to have a narrative that fit”—about his home and culture, and himself—“and not quite having recourse to one.”

He found it in a class on Islamic culture in contemporary societies, taught by professor of Indo-Muslim and Islamic religion and cultures Ali Asani. For the first time, Sethi learned about the role the arts had always played in Muslims’ understanding of their faith. He learned that Islam was not only politics and theology but what Asani called “heart-mind knowledge”: that before it was codified into scripture, the religion had begun as an aesthetic tradition that sought “to explain God through beauty.” The class unlocked something in Sethi.

He began to see the old folksongs he’d grown up with in a new light—ghazals (love poems) and qawwalis (devotional songs) handed down by the Sufis, Islamic mystics whose practice emphasizes pluralism, tolerance, and an inward search for the divine. He’d heard them embedded in movies and advertisements and jingles on the radio—“just a part of our cultural DNA”—but they’d always seemed separate from religion, and lesser; now he understood they were neither.

Sethi performs on Coke Studio, a popular live-music TV show in Pakistan that he says "gives young people something to hold onto—amid religious and political strife."

Photograph courtesy of Ali Sethi and Coke Studio

He abandoned his planned economics focus and began pursuing music and creative writing, concentrating in Sanskrit and Indian studies (and shortly after graduating, published a well-received, semi-autobiographical novel, The Wish Maker, about politics and family in Pakistan). He bought a harmonium and during summers in Lahore began apprenticing under classical singers Ustad Naseeruddin Saami and Farida Khanum, embarking on the rigorous art of singing ragas, a complicated structure for melodic improvisation in which shifting notes can sound almost molten. “The music is never fixed,” he says. “A raga is almost like a melodic being. You have to breathe life into it, and every rendition, every performance, may be different.”

In traditional music, he has found room for musical experimentation and an avenue for his own “language of dissent.” Sufi songs, in particular, lend themselves to multiple interpretations; the same verses, Sethi says, may be read as the story of a love affair, or a heartbroken letter to an unjust society, or a dialogue with the divine. For centuries, Sufi poets have dealt with topics like gender identity, sexuality, cultural difference, and political strife. “The poems are so extremely inclusive,” he says. “And the appetite for Sufi music in Pakistan allows people like me to get away with a lot of potentially subversive stuff through the metaphors of Sufi poetry—these beautiful, deliberate ambiguities.”

“Chandni Raat,” a single from his forthcoming album, illustrates what he means. Sung in Hindi, it takes its refrain from a ghazal by Saiffudin Saif: “This moonlit night has been a long time coming / The words I want to say have been a long time coming.” “The implication is of something half-veiled, half-visible,” says Sethi, who added his own lyrics that gesture toward an unspecified union, and set the song to a soft, slow melody adapted from two ragas. The music video shows a spectral, ruined train station and a collection of stranded passengers who gradually warm to each other across differences in age, religion, ethnicity, sexual identity, across different walks of life. “There’s a transgender person,” Sethi says. “They’re all residents of Lahore, people who embody the multiple interpretations of this poetry and music.” Three days after the video was released on YouTube last February, an unexpected skirmish flared up between Pakistan and India, and the two countries seemed briefly on the verge of war. The video’s comment section flooded with listeners writing from each side of the border, preaching peace and togetherness, praising the song’s message of love. “It became kind of an anthem,” Sethi says. “It felt genuinely miraculous.”

A similar spirit animates a concert series that Sethi and Asani present together in cities around the world, “The Covenant of Love”—from a Quranic phrase describing God’s relationship with humanity. Sethi and his band perform songs by legendary Sufi poets, while Asani, seated onstage, explains their history and symbolism. This was the show Sethi brought to Sanders last spring, and before the musicians played “Dama Dam Mast Qalandar,” Asani told the audience about a 2017 suicide bombing at the shrine that killed 90 worshippers. “But the next day, people were back, dancing,” he said, a testament to poetry’s power to give courage and spiritual solace. And then he invited students to their own version of dhamal. “If the spirit moves you, just dance.”