If the women’s suffrage movement took place today, what would it look like? Radically different, surely, from the way it did in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when its organizers rode through the country on horseback, shouted through town squares, dropped leaflets from airplanes, and marched in neatly choreographed pageants to spread the word about their cause. Today’s world of online activism can feel deprived of that vitality—which makes Susan Ware’s Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote, all the more of a delight for a modern reader. Ware tells a new history of women’s suffrage through portraits of 21 women (and one man) both famous and obscure, from the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention through the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

“How can someone demand the vote without having that basic political right in the first place?” asks Ware, Ph.D. ’78, an independent scholar of women’s history and associate of Harvard’s history department. Part of the answer is that the suffragists were intrepid and relentless. They were the first political protesters to picket the White House (and to burn President Woodrow Wilson in effigy), for which nearly 500 were arrested and 170 went to prison between 1917 and 1919. Authorities were cracking down on dissent during World War I—and the activists were considered disloyal to the war effort. In the summer of 1918, after a group of suffragists were arrested and released on bail, they resumed their protests immediately and were arrested again and again.

One of them, Hazel Hunkins, cabled her anxious family in Montana: “TWENTY SIX OF AMERICAS FINEST WOMEN ARE ACCOMPANYING ME TO JAIL ITS SPLENDID DONT WORRY LOVE HAZEL.” Their experiences provided the women a sense of camaraderie resembling that of men in war; both suffering and exhilaration were entangled in the horrid and humiliating conditions in prison. Hunkins returned home in an ambulance and, one friend wrote, “violently ill.” They were honored by the National Women’s Party, one of the two major organizations orchestrating the suffrage fight, with brooches in the shape of a prison cell.

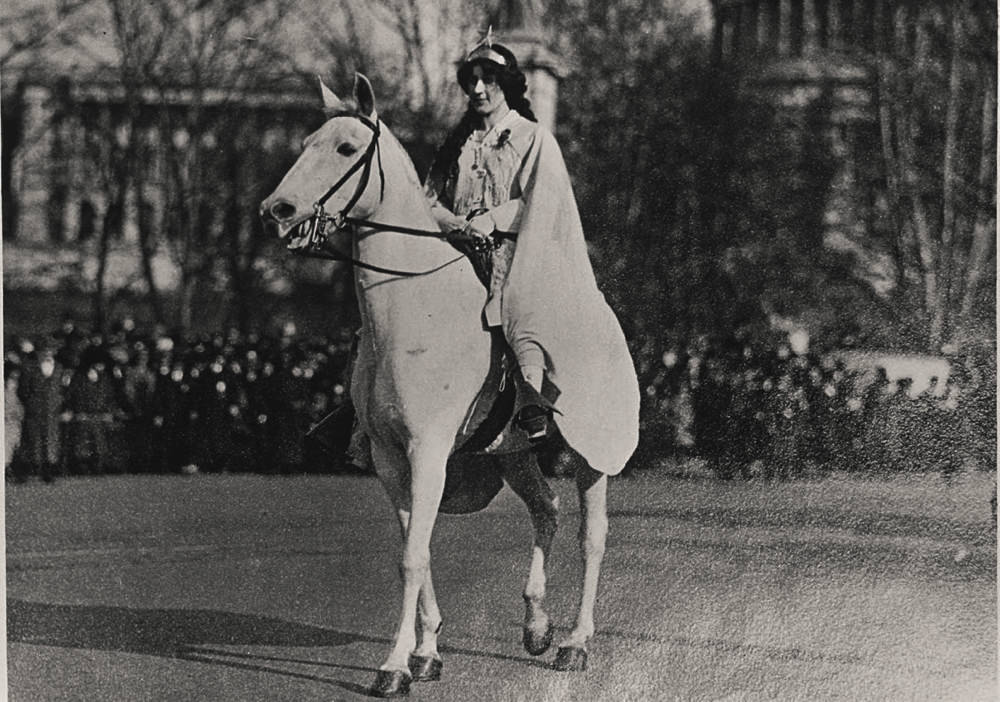

Inez Milholland leads the 1913 suffrage parade in Washington, D.C.

Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

For the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, Ware wanted to tell a broader, more inclusive story about “woman suffrage,” as it was known then. A common narrative about the suffragists, she said in an interview, is that they were racist, wealthy white women—and many of them were. They mirrored the racism of American society, organizing segregated parades and disparagingly objecting that black men had been granted the vote before them. And it was largely only the wealthy who had the ability to volunteer their time. But this narrative, Ware argues, erases the history of both black suffragists who sought to integrate race and gender into the movement and working-class suffragists who saw the vote as an important tool for the urban poor, many of whom were women. As its portraits encompass women from different class, race, and religious backgrounds, Why They Marched provides glimpses of the movement’s connections to many questions about the fabric of society: the rights of factory workers, the relationship between patriarchy and white supremacy, and what it means to be female.

At the dawn of the modern period, it was not just received ideas about the role of women, but also new anxieties about the social shifts under way in an industrializing America that shaped the public’s fear of woman suffrage. Rose Schneiderman, a famous socialist and union organizer, had an answer to the popular claim that participating in politics would “unsex” women: “Surely…women won’t lose any more of their beauty and charm by putting a ballot in a ballot box once a year than they are likely to lose standing in foundries and laundries all year round.”

It was largely only white women, Ware says, who won the vote in 1920: black women (like black men) remained mostly disenfranchised until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. One of the most remarkable women Ware profiles, Mary Church Terrell, was the daughter of former slaves who eventually became wealthy members of Memphis’s black elite. She urged the leadership of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) to include the interests of black women on its agenda (often to little effect), and was active in women’s rights movements in Europe, where she informed international audiences about the status of African Americans. Terrell spoke about race, gender, and power with a piercing clarity that rings true a century later. At a convention of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom in Zurich, where it was reported that there were women from all over the world, she remarked: “On sober, second thought, it is more truthful to say that women from all over the white world were present.”

The United States that deprived women of the vote might seem unrecognizably distant to contemporary readers. But it was only 100 years ago that suffragists were camping out in Washington, lobbying Congressmen to pass the constitutional amendment that guaranteed them this foundational right. In the Senate, it squeaked by with only a narrow margin. How can we comprehend the radical transformation of many women’s social and political status in such a short period?

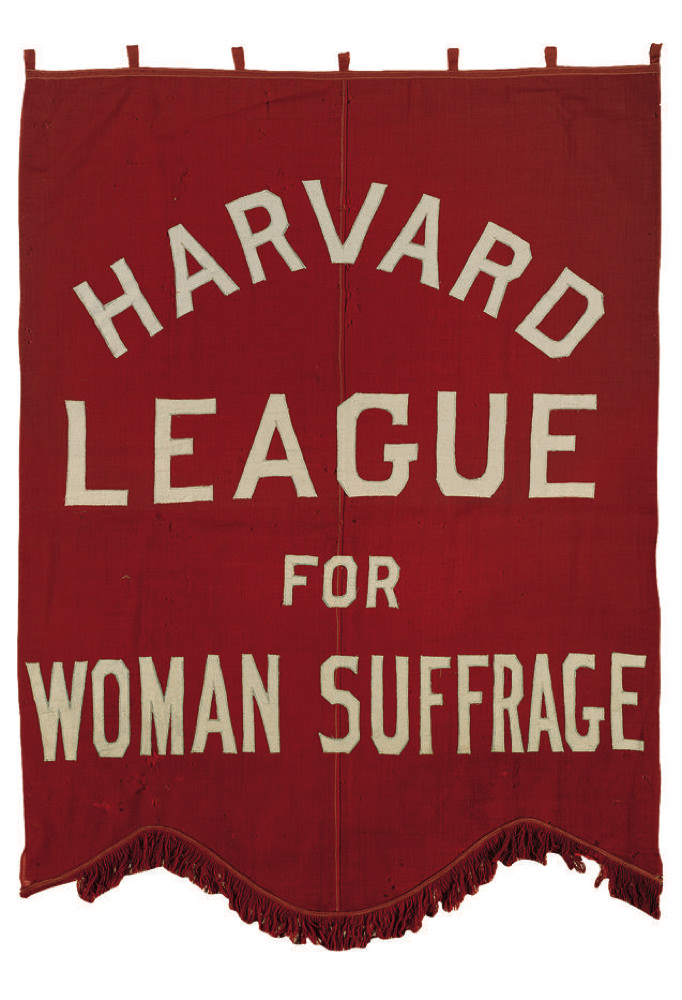

The banner of a men’s group that supported women’s right to vote.

Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

Here, Why They Marched falls short. Ware explains that the suffrage movement was closely connected to Reconstruction and the Fifteenth Amendment that granted the vote to African-American men: “The Civil War and its aftermath put questions of citizenship and human rights firmly on the national agenda,” she writes. “In this fraught but pregnant political moment, women activists believed they might have a fighting chance to win those rights for women as well.” These important points lay the groundwork for Ware’s recurring discussion of the relationship between race and gender in the suffrage movement. But as an explanation for the emergence of suffrage and the larger feminist movement, they feel incomplete. Women had been talking about their political rights long before the Civil War, alongside discussions about the abolition of slavery and other movements that eventually transformed society. A broader sketch of the economic history of the United States and Europe during this period, including industrialization and the rise of wage labor, might provide a richer explanation for the conditions that shaped the minds of suffragists, and made women’s liberation possible.

But the book does not attempt to be a definitive or intellectual history of suffragism. It is a focused, slim volume that allows Ware to zoom in on the lives of her suffragists; within their vivid stories are many surprises about what kinds of women were demanding the vote, and why. The earliest states to grant women suffrage were not on the East Coast, but those on the Western frontier: Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, and Idaho. Emmeline B. Wells, a prominent, early Mormon suffragist, was nevertheless excluded from leadership roles in the movement because she was the seventh wife of a polygamous husband; Mormon women’s activism, Ware writes, “was quickly forgotten.”

Ware’s analysis recognizes that gender is so complex, so entangled with the structure of society, that it’s impossible to exclude women who participate in patriarchy from an honest feminist history. Her effort to dust off these stories provides a messier, sometimes troubling, and more convincing picture of some of the women who changed the world.