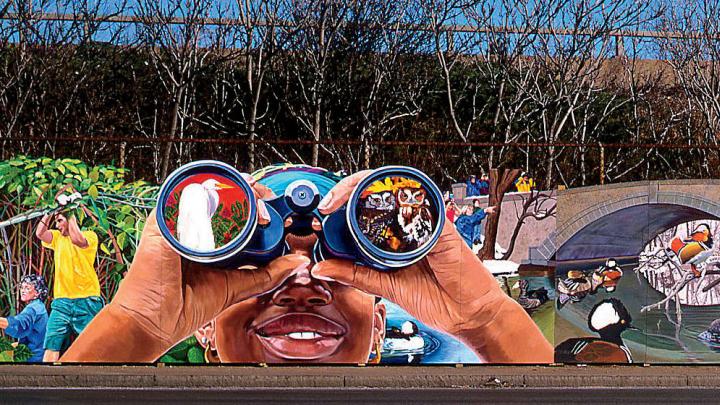

It’s the most unlikely of galleries—a concrete retaining wall in the shadow of Interstate 93, just outside Boston. But David Fichter ’73 is a full-time muralist. His work (davidfichter.net) appears in school cafeterias and train stations. It overlooks parking lots and playgrounds. Brick walls are his canvas and his preferred surface (for their “urban texture”), although he’s also painted on cinder block, stucco, Sheetrock, and the panels of multiple density overlay (MDO; specially treated wood impregnated with resin) that make up the Mystic River Mural Project. Begun in 1996, with a section added each summer by Fichter and a group of a dozen or so local teens, the mural depicts the life of the river in his trademark teeming, cornucopia-like style, with so many layers of distance and perspective that the effect is nearly three-dimensional. Recently, a panel had to be restored after an encounter with a speeding car—one of the hazards when your museum is outdoors.

Early on, Fichter, a fine-arts concentrator who studied set design with Franco Colavecchia, experimented with different artistic styles and painted political posters (he turned his Lowell House dorm room into a silk-screening studio during the 1973 graduate-student strike). Then a friend told him to visit Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco’s Epic of American Civilization at Dartmouth College’s Baker Library. Fichter subsequently traveled throughout Latin America, where murals have a rich history as a form of social commentary. “Murals have always spoken to me as a way to push change in society without shoving it down people’s throats,” he says. “What I like is that people can find their way in—they feel empowered when they participate in the process or see themselves or their stories represented in public.”

There was no place to study mural painting formally, but a contact with Victor Canifru, a Chilean muralist living in Nicaragua, opened the door to Fichter’s first commission, at a school in Managua. And then? “I was hooked,” he says. He’s now completed more than 200 projects, the majority in Massachusetts, although his work has also taken him to locales like Wayne, Michigan (an historical mural of the city’s deep connections to the automotive industry), and Madison, Wisconsin (a mural on the study of water science for the University of Wisconsin).

With an approach that blends the personal and public, Fichter generally works with neighborhood organizations or public officials to determine a work’s overall design, a process that can involve a fair amount of give and take. On average, the lifespan of a project from start to finish is about one year. “I like to do work that comes out of lived experience,” he says—which involves gathering oral histories and spending time in the community. “There’s always a negotiation between ideas and images,” he adds. “Weaving in my own story and connections helps inspire me.”

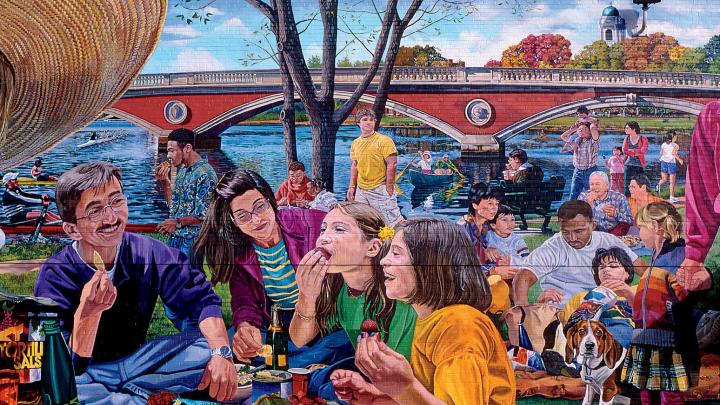

In Sunday Afternoon on the Charles, for example, a commission for the Trader Joe’s grocery store on Memorial Drive in Cambridge, Fichter can point out friends, neighbors, and his neighbor’s beagle, Tyler. A blonde, straw-hatted toddler eating a peach separates a colorful Cambridge present from a black-and-white Harvard Square of the past; the toddler is Fichter’s younger daughter, Olivia Wise, now 19 years old. A young girl with a bow in her hair in the black-and-white section is his “muse” and neighbor Suzanne Green, a lifelong Cantabrigian who will turn 99 this year.

The world of muralists is relatively small and familial, with plenty of information shared on the technical aspects of paint (which brands and colors best survive the elements) and the ins and outs of surface preparation. “There’s a conservationist aspect to it,” says Fichter. “If a wall is painted, I try to find out what’s already on there to see how it will react with what I’m planning to add.” An outdoor mural usually requires a touch-up after 15 years or so. One of Fichter’s oldest pieces is Bread and Roses (1985), for the Greater Lawrence Family Health Center in Lawrence, Massachusetts.

After determining the general design, Fichter makes a scaled drawing on paper and overlays it with a numbered grid (typically, one inch to one foot) that he uses as a guide when painting. “It becomes abstract,” he says. “I don’t think, ‘I’m working on an eye.’ You can really get lost.” For an indoor mural, he may make a transparency of an image, project that onto the wall, and paint from there. Sometimes he listens to history books on tape as he works—he finds music too distracting.

The fishbowl aspect of working in the public eye often leads to serendipitous encounters. One day, a local resident wearing an EAT T-shirt wandered by and asked to be included in a commission for Cambridge’s Area 4 Neighborhood Coalition. It was the perfect impromptu addition to The Potluck, which shows a multiethnic gathering of Central Square residents enjoying a meal together.

“This was a never-ending project,” Fichter says fondly. “So many people came by to ask if they could be in it.” If they lived in the neighborhood, he considered their request. (Fichter himself lives just a few streets away.) The 22-by-100-foot mural used about 20 gallons of acrylic paint and took four months to complete with the help of volunteers. He focuses on the larger elements, while volunteers work on smaller pieces, giving an overall effect of unity.

That collaborative aspect is an important part of the process for him, despite the challenge of coordinating different talents and personalities. “It becomes a very engaging experience for people, even people who aren’t artists,” Fichter says. “I’ve likened it to religion. There’s a real sense of withdrawal when the project is complete.”